Links

- STOP ESSO

- The One and Only Bumbishop

- Hertzan Chimera's Blog

- Strange Attractor

- Wishful Thinking

- The Momus Website

- Horror Quarterly

- Fractal Domains

- .alfie.'s Blog

- Maria's Fractal Gallery

- Roy Orbison in Cling Film

- Iraq Body Count

- Undo Global Warming

- Bettie Page - We're Not Worthy!

- For the Discerning Gentleman

- All You Ever Wanted to Know About Cephalopods

- The Greatest Band that Never Were - The Dead Bell

- The Heart of Things

- Weed, Wine and Caffeine

- Division Day

- Signs of the Times

Archives

- 05/01/2004 - 06/01/2004

- 06/01/2004 - 07/01/2004

- 07/01/2004 - 08/01/2004

- 08/01/2004 - 09/01/2004

- 09/01/2004 - 10/01/2004

- 10/01/2004 - 11/01/2004

- 11/01/2004 - 12/01/2004

- 12/01/2004 - 01/01/2005

- 01/01/2005 - 02/01/2005

- 02/01/2005 - 03/01/2005

- 03/01/2005 - 04/01/2005

- 05/01/2005 - 06/01/2005

- 06/01/2005 - 07/01/2005

- 07/01/2005 - 08/01/2005

- 08/01/2005 - 09/01/2005

- 09/01/2005 - 10/01/2005

- 10/01/2005 - 11/01/2005

- 11/01/2005 - 12/01/2005

- 12/01/2005 - 01/01/2006

- 01/01/2006 - 02/01/2006

- 02/01/2006 - 03/01/2006

- 09/01/2006 - 10/01/2006

- 10/01/2006 - 11/01/2006

- 11/01/2006 - 12/01/2006

- 12/01/2006 - 01/01/2007

- 01/01/2007 - 02/01/2007

- 02/01/2007 - 03/01/2007

- 03/01/2007 - 04/01/2007

- 04/01/2007 - 05/01/2007

- 05/01/2007 - 06/01/2007

- 06/01/2007 - 07/01/2007

- 07/01/2007 - 08/01/2007

- 08/01/2007 - 09/01/2007

- 09/01/2007 - 10/01/2007

- 10/01/2007 - 11/01/2007

- 11/01/2007 - 12/01/2007

- 12/01/2007 - 01/01/2008

- 01/01/2008 - 02/01/2008

- 02/01/2008 - 03/01/2008

- 03/01/2008 - 04/01/2008

- 04/01/2008 - 05/01/2008

- 07/01/2008 - 08/01/2008

Being an Archive of the Obscure Neural Firings Burning Down the Jelly-Pink Cobwebbed Library of Doom that is The Mind of Quentin S. Crisp

Friday, September 29, 2006

The Story of Story

After finishing my novella Shrike, I have returned to the mammoth task of writing and word-processing my novel Domesday Afternoon. It is very long and looks like becoming a series of novels rather than a single novel. I have written over a thousand pages now in longhand, and have decided to stop at the nearest convenient break in the story, word-process the whole thing, and edit it. Hopefully, in the process of doing so I shall also be able to untangle a few kinks in the plot and so on (which is not to say the plot will become any less kinky). Anyway, I thought I would paste an extract from the novel below. There are basically two strand to the novel. Graham South is a survivor in a post-deluge world, and he is writing a story about the world before the deluge. I still don't know how to indent paragraphs with HTML etc. so, much as I hate the format, I will have to separate each paragraph with a space. Here it is:

I have called this great attempt “the autobiography of the soul”, and have explained that this means the story of my life as it should have been, rather than as it was. In other words, it has been my intention to try and capture that ultimate, exquisite daydream that usually hovers about the corner of the mind’s eye and vanishes like mist in sunlight when I try to view it too directly. Having explained my intention again in such terms, its futility seems self-evident. Still, something has been bothering me as I have progressed in my story, and, self-evident or not, I feel the need to interrupt my story again to explain that something. Stated simply, the perplexing question runs like this: if I have been intent only on fleshing out into its fullest realisation my ultimate daydream, why is it that my hero, Joe Manser, is afflicted with crippling shyness and tormented by continual disappointments? Well, I suppose, for one thing, many fairy tales begin with a similarly wretched protagonist – Cinderella, the ugly duckling, the Beast from the tale Beauty and the Beast, and so on. For another thing, I have to recognise my own failure and defeat in the hero before I can proceed to enjoy his redemption. But even these two answers are not quite satisfactory. They anticipate some future change within the story. Even as I write I have no way of knowing if I will get that far. I know, have known since before I picked up a pen, that this manuscript could come to an end at any moment. I have had to write in the knowledge that this will probably be a fragment and may never be read by another living soul. I am not writing a tale of gritty reality – in other words, nightmare – that becomes a tale of dream and wish-fulfilment, even if I might seem to be. No, this is certainly daydream from start to finish, daydream in all places. If we – I – examine the actual incidents that form the story, we – I – discover that so far, although they are not literally and in all details autobiographical, there is nothing here that violates a sense of reality, and nothing here, perhaps, that anyone would particularly wish to experience as reality. So why do I call this daydream – the ultimate and most exquisite daydream? These unremarkable events become daydream in the mere act of telling them. As to why these particular events are more exquisite than any others – I am unable to answer that question at present, and can only pass it over by saying it is ‘the mystery of the soul’. Let me go back to the first answer: events become daydream in the mere act of telling. The easiest and oldest way to access the timeless eternal, to bestow immortality, to become god, is simply to tell a story. And in order to bestow immortality on this idea, which, anyway, is not new, I should like to recount its history. If only I had any of my books with me! But they are either lost beneath the waves, or left to rot on a hillside in France, or, a few of them are back at Scragshore Village, or in the Domesday Library. As usual, all I have is my own soft and time-addled brain on which to rely. Anyway… anyway… this is the story of story, of how mythology became religion became entertainment – animism to monotheism to post-modernism. I shall do as traditionalists once urged, by starting at the beginning; but I shall also confound them, because it is not the beginning at all:

"In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God."

Language was the first mirror of the human race. Man looked in this mirror, saw his reflection and became aware of himself for the first time. He called this reflection ‘God’. At least, this is the crude and obvious analogy that I must use for the sake of convenience. The word was there in the beginning because it was the beginning. Without words there could be no time and thus no beginning. Once upon a time – the start of every story.

However, here in this cave on a scrag of ragged rock at the other end of history, it seems unlikely to me that the beginning was truly so instantaneous. Which came first – the chicken or the egg? The meaning or the word? All we know of ancient languages are the physical traces of scripts, and the earliest of these are pictorial in nature – the hieroglyphs of Egypt, the ideograms used in the various languages of China, the cuneiform of Mesopotamia. Before these the traces left – like the Palaeolithic paintings on the walls of the Lascaux caves – were less language and more picture. From picture to language. Were these earlier pictures of bison and hunters also, then, a form of language? If a language is a system of signifiers whose use makes thought possible, then surely they were. Did men first think in pictures? And what is thinking in pictures if it is not dreaming? Language, perhaps, came first from the well of dream. And now, at the other end of history, here I am using language to try and dream again. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Language, in those early days when dreamtime and wordtime were still intermingled, was surely a sacred thing. There could have been no division between the spiritual and the secular. The practical matter of the day was the hunting of bison, which was also the sacred, life-giving ritual told of in the practical, sacred language of the wall paintings. Then, for me to say that telling of something in story automatically rendered it an immortal dream would be meaningless, because no one would know that the world could be otherwise. Of course the language that told the story was magical! Of course it was godly! And this, retrospectively, we might call animism. Everything is alive, the signifier of its own godhead.

At first, perhaps, signifiers sprang up naturally as images from the well of dream. But as those signifiers were put to increasingly various use they must have become independent. The abstract was born in the space between the separated signified and signifier. The signifier began to assume increasing importance. With the growth in the complexity of language, time also began to shift and flow. It left behind strata. Elementals of bison, waterfall, hill and tree became gods of polytheistic mythology, who lived through language, and therefore in time, and thus living, died, and became fossils. The sacred became abstract and withdrew to fill the great, unseen emptiness behind the sky. This was monotheism. God and man were as separate as the very words ‘God’ and ‘man’ and the now abstracted, one might say Platonic, meanings they signified. Yet in all this division the sacred did exist. What was important was to exist in the correct syntactical relation to one’s God. Even if all words are separate, as long as they are all in the right place, creation is redeemed; “The snail is on the thorn; God’s in his Heaven – all’s right with the world!” Religion is the syntax that binds one meaning to another, and it is the over-arching narrative that guarantees a happy ending to those words with positive associations (those with negative associations must suffer eternal hell). Religion in this case is story taken literally. The story, though separated from the world by the gulf of abstraction, still retains the authority of the sacred; it is at once a story and life itself. Therefore, to lay down one’s life for the story is to regain that life a thousandfold. The reality of the story reinforces the reality of life, the reality of Earth that of Heaven and, on both counts, vice versa. This life matters because Heaven, too, matters. This life is real because Heaven, too, is real. Stated once more, briefly – the story is real.

Exactly why this form of religion fell I cannot now say, though retrospectively it appears inevitable. Perhaps it was for the same reasons that the polytheistic gods of mythology became fossilised – the natural action of language-quickened time. Or perhaps such an explanation is too vague and glib. Perhaps the newly complex language of religion was torn apart by the intolerable opposites of eternal Heaven and eternal Hell. In any case, it did fall. Not that it disappeared entirely. The great Word-God of religion simply suffered a collapse in which vast chunks of its body were broken and scattered, forming numbers of people who could not agree on the meaning of the words they used or the principles behind them. Those who preached that the story of the Word-God was universal were now preaching a self-evident absurdity. This was the age not of the universal, but of the individual. If I recall correctly, it was called first ‘modernism’ and then ‘post-modernism’, though I am now unsure of the difference between the two. ‘Modernism’, I believe, was basically a transitional period – I suppose all periods are – representing the mourning of mankind for the death of the Word-God and of universality. It was a tragic age. The only stories left to tell were the confessions of godless individuals. Post-modernism was simply life after the tragical catharsis of mourning had passed. The Word-God was dead and his corpse was the breeding ground for countless worms. This was the age of consumerism. Instead of religion there was entertainment.

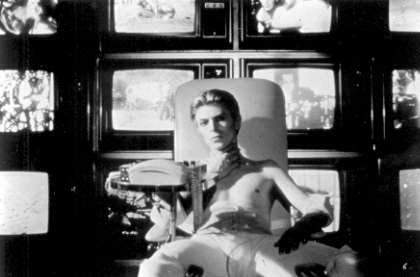

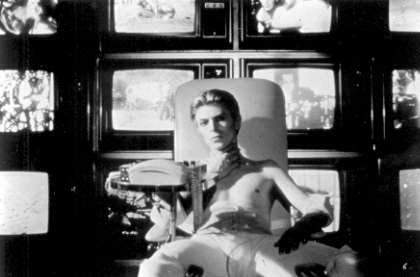

Perhaps the ultimate symbol of post-modernism is television. If there was no God now to grant us immortality, then we had to attain it by other means. We surrounded ourselves with a glowing forcefield of picture-boxes to keep out death. These were like the mirror that language and story had once been, except that the images they showed were not really our own. Where once religion had made us immortal by rendering both life and after-life equally real, now television made us immortal by rendering everything – life and after-life – equally unreal. Nothing now was real. We sat in front of the picture-box that was television and watched people shoot each other in distant lands on the news while we ate our dinner, and when the news was over we watched actors shoot each other in distant lands, or near. Finally, it made no difference. Television turned the very fabric of life into fiction. If someone died or some terrible disaster took place, it did not matter, because it was all part of a safe, fictional existence made stable by having been recorded, broadcast and watched – thus receiving the redeeming official stamp of the broadcasting corporations.

Of course, there were problems with this form of immortality, too. Reality, in that age, was associated with concrete – the grey substance with which we built our roads and cities. But this association of reality with concrete was precisely the lie by which we tried to trick our way to immortality, just as we tricked ourselves by saying that we ‘fought for peace’. Concrete was, in fact, the very opposite of reality. It was what cut us off from the world, from the very earth beneath us, and from death, since it was designed to create a sterile, insulating safety zone. It was concrete that rendered all things unreal. We had glimpses of this when cracks appeared in the concrete and death came through in violent, gut-churning forms that the drama of television, always dignifying each death and disaster with incidental music, had not prepared us for. We knew when we saw the cracks of violence that the safe immortality of post-modernism was a lie. We knew, and we felt sick.

But perhaps one of the aspects of post-modernism that interests me most as a story-teller, is what has been called ‘the aesthetics of plenty’, but what I would like to call ‘the junction of parallel worlds’.

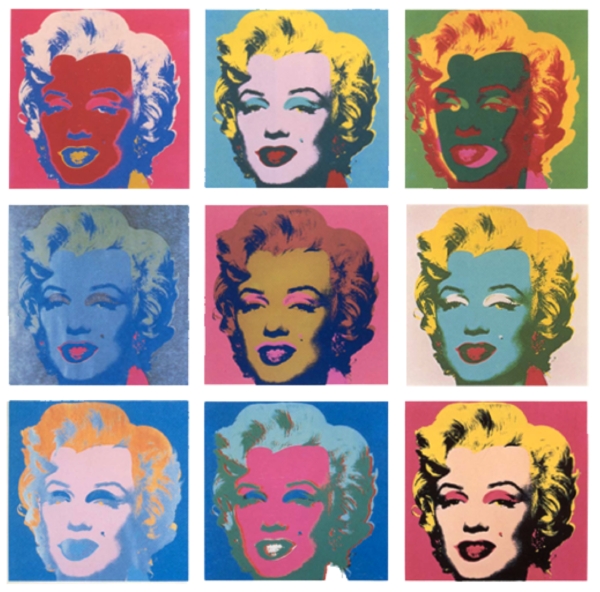

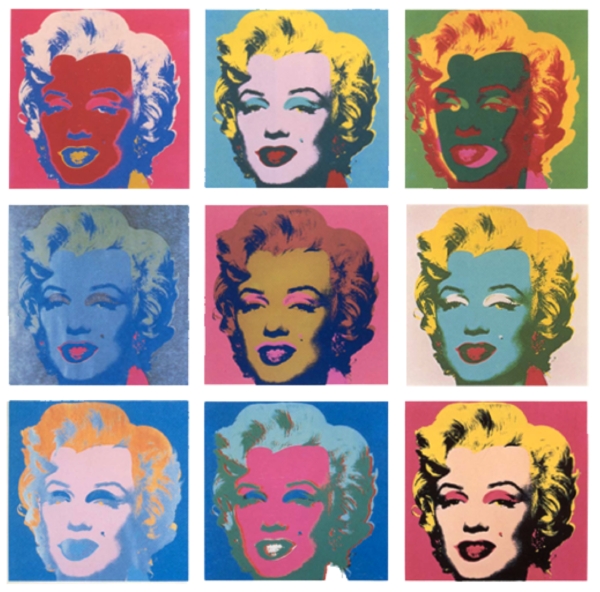

The beginning of post-modernism, like the beginning of story and time itself, is difficult to pin-point. One possible beginning of many is the movement known as Pop art, which took place at the start of the second half of the twentieth century. In fact, it is in relation to Pop art that the term ‘an aesthetic of plenty’ was commonly used. Some of the best-known practitioners of this art were Eduardo Paolozzi, Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol. In Warhol’s work in particular, we may discern some of the principle mechanisms behind the aesthetic. One work consists simply of the face of screen idol Marilyn Monroe reduplicated many time to form a grid of faces. The idea of plenty is here explicitly associated with the world of fame and the fictions of films. Film – which would become television – is the fountainhead of plenty, since it is a portal to a world whose resources are absolutely inexhaustible. As if to prove this inexhaustibility, Warhol has given us not one Monroe, but many, in a symbolic gesture at infinitude. At the same time, none of these are depictions of the ‘real’ Monroe. They are two-dimensional images whose source is a two-dimensional image. The implication is that there is no original; there are only copies. This is another way of restating my earlier formula – post-modernism gave us immortality by making everything unreal. The inexhaustible ‘plenty’ was another manifestation of immortality’s eternity. Another effect of this reduplication was the destruction of the gap in value between ‘real’ and ‘fake’, ‘original’ and ‘copy’. Perhaps this could be seen as a flat and sterile reflection of animism, in which all things were equally alive and sacred. In Pop art, all things were equally works of art.

Another of Warhol’s works plays the same trick with a can of Campbell’s soup. It is reduplicated in symbolic plenty, in the same way as Monroe’s face. Perhaps the very idea of this reduplication came from seeing cans of soup piled up this way in a supermarket. In any case, viewing the two works next to each other it is easy to draw a parallel between the ‘plenty’ of fame and the ‘plenty’ of mass production and consumerism. This was the mass production that had its inception over a hundred years earlier in Britain’s Industrial Revolution, which one English poet spoke of ominously at the time, naming its manufacturing mills “dark” and “Satanic”.

Warhol’s symbolic gesture in creating these images was to form the template of human culture for over half a century.

In order to describe this aesthetic of plenty with greater clarity, I would like to now name what I believe to be its antithesis – Buddhism. Buddhism was – I do not know for certain whether any adherents survive – a mode of religion that began in India at some time around 500 BC. From there it spread eastward across the continent of Asia until finally it arrived at the Japanese archipelago. One of the forms of Buddhism to emerge in Japan, and perhaps the most famous form in the West – though it was, in fact, based upon the Chan Buddhism of China – was Zen. This was a particularly abstract and ascetic form of the religion and was probably responsible for the minimalism associated with traditional Japanese aesthetics. Where does this minimalism spring from within Buddhist doctrine? All life is suffering. All suffering is caused by desire. Therefore, the only way to overcome suffering is by extinguishing desire. The extinguishing of desire, indeed, of the very self that is the source of desire, is called Nirvana. And how is Nirvana described? It is a state of non-existence, which is, perhaps, as minimalistic as it is possible to be. Non-existence, apparently, is much misunderstood. But since I do not understand it myself, there is little point in trying to explain where the misunderstanding deviates from the truth. Suffice it to say, Nirvana seems to be a form of accepting the world as it is by living completely in the here and now. In that sense, Buddhism is the enemy of both art and consumerism. The artist, after all, is driven by desire. He has a vision of another world, a better world, and he tries to conjure it in his art. Consumerism, likewise, and even more obviously, is based upon desire. Artists and consumers both, are caught in the world of illusory form that the Buddhists called ‘Samsara’. Instead of accepting the world as it is, they are bent on multiplying the forms of Samsara by any means possible. It is intolerable that any idea should be left unrealised, any invention left unmade, any role left unplayed, any story unwritten, any life unlived. They must leave no stone of existence unturned; they must exhaust all possibilities. To do otherwise is, I repeat, intolerable. And thus, at the height of this post-modern aesthetic of plenty, the shelves of supermarkets were filled with a hundred different kinds of toothpaste and shampoo and breakfast cereal, and the television stations bred like a virus, multiplying the mirror of possible realities to shield us against death. This was the spaghetti junction of parallel worlds. But the plenty, it seems, is now past. The junction is behind us. We are on single, narrow roads again.

And that is the story of story so far. It has reached an uncertain stage indeed, but I hope that by writing about it in this way I will affirm its sacred and eternal nature.

Two things occur to me now that I have written this metastory. The first is that the immortalising quality of story might be precisely the reason I cannot seem to write this as if there is no audience. Maybe such a thing is impossible by definition, since a story implies the ultimate audience of ‘a god’. And yet I wish I could write as if there were no audience. Perhaps then, at last, I would break through to reality. Am I, then, still infected by the post-modernism that made all things unreal?

The second thing that occurs to me is that none of this has really answered my greatest and most personal question – If language and story came originally from the wellsprings of the sacred in the real world, why is it that I feel my soul is in story, but nowhere in the life I have lived in this world? I seem to be saying that my soul alone is different and precious, that my soul is a world that never existed. Is that possible? It’s like saying that the ultimate god (or the ultimate truth) is an outsider with no home in existence. Or that the ultimate god is a single damned individual. But yes, that is how I feel.

A single damned individual.

After finishing my novella Shrike, I have returned to the mammoth task of writing and word-processing my novel Domesday Afternoon. It is very long and looks like becoming a series of novels rather than a single novel. I have written over a thousand pages now in longhand, and have decided to stop at the nearest convenient break in the story, word-process the whole thing, and edit it. Hopefully, in the process of doing so I shall also be able to untangle a few kinks in the plot and so on (which is not to say the plot will become any less kinky). Anyway, I thought I would paste an extract from the novel below. There are basically two strand to the novel. Graham South is a survivor in a post-deluge world, and he is writing a story about the world before the deluge. I still don't know how to indent paragraphs with HTML etc. so, much as I hate the format, I will have to separate each paragraph with a space. Here it is:

I have called this great attempt “the autobiography of the soul”, and have explained that this means the story of my life as it should have been, rather than as it was. In other words, it has been my intention to try and capture that ultimate, exquisite daydream that usually hovers about the corner of the mind’s eye and vanishes like mist in sunlight when I try to view it too directly. Having explained my intention again in such terms, its futility seems self-evident. Still, something has been bothering me as I have progressed in my story, and, self-evident or not, I feel the need to interrupt my story again to explain that something. Stated simply, the perplexing question runs like this: if I have been intent only on fleshing out into its fullest realisation my ultimate daydream, why is it that my hero, Joe Manser, is afflicted with crippling shyness and tormented by continual disappointments? Well, I suppose, for one thing, many fairy tales begin with a similarly wretched protagonist – Cinderella, the ugly duckling, the Beast from the tale Beauty and the Beast, and so on. For another thing, I have to recognise my own failure and defeat in the hero before I can proceed to enjoy his redemption. But even these two answers are not quite satisfactory. They anticipate some future change within the story. Even as I write I have no way of knowing if I will get that far. I know, have known since before I picked up a pen, that this manuscript could come to an end at any moment. I have had to write in the knowledge that this will probably be a fragment and may never be read by another living soul. I am not writing a tale of gritty reality – in other words, nightmare – that becomes a tale of dream and wish-fulfilment, even if I might seem to be. No, this is certainly daydream from start to finish, daydream in all places. If we – I – examine the actual incidents that form the story, we – I – discover that so far, although they are not literally and in all details autobiographical, there is nothing here that violates a sense of reality, and nothing here, perhaps, that anyone would particularly wish to experience as reality. So why do I call this daydream – the ultimate and most exquisite daydream? These unremarkable events become daydream in the mere act of telling them. As to why these particular events are more exquisite than any others – I am unable to answer that question at present, and can only pass it over by saying it is ‘the mystery of the soul’. Let me go back to the first answer: events become daydream in the mere act of telling. The easiest and oldest way to access the timeless eternal, to bestow immortality, to become god, is simply to tell a story. And in order to bestow immortality on this idea, which, anyway, is not new, I should like to recount its history. If only I had any of my books with me! But they are either lost beneath the waves, or left to rot on a hillside in France, or, a few of them are back at Scragshore Village, or in the Domesday Library. As usual, all I have is my own soft and time-addled brain on which to rely. Anyway… anyway… this is the story of story, of how mythology became religion became entertainment – animism to monotheism to post-modernism. I shall do as traditionalists once urged, by starting at the beginning; but I shall also confound them, because it is not the beginning at all:

"In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God."

Language was the first mirror of the human race. Man looked in this mirror, saw his reflection and became aware of himself for the first time. He called this reflection ‘God’. At least, this is the crude and obvious analogy that I must use for the sake of convenience. The word was there in the beginning because it was the beginning. Without words there could be no time and thus no beginning. Once upon a time – the start of every story.

However, here in this cave on a scrag of ragged rock at the other end of history, it seems unlikely to me that the beginning was truly so instantaneous. Which came first – the chicken or the egg? The meaning or the word? All we know of ancient languages are the physical traces of scripts, and the earliest of these are pictorial in nature – the hieroglyphs of Egypt, the ideograms used in the various languages of China, the cuneiform of Mesopotamia. Before these the traces left – like the Palaeolithic paintings on the walls of the Lascaux caves – were less language and more picture. From picture to language. Were these earlier pictures of bison and hunters also, then, a form of language? If a language is a system of signifiers whose use makes thought possible, then surely they were. Did men first think in pictures? And what is thinking in pictures if it is not dreaming? Language, perhaps, came first from the well of dream. And now, at the other end of history, here I am using language to try and dream again. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Language, in those early days when dreamtime and wordtime were still intermingled, was surely a sacred thing. There could have been no division between the spiritual and the secular. The practical matter of the day was the hunting of bison, which was also the sacred, life-giving ritual told of in the practical, sacred language of the wall paintings. Then, for me to say that telling of something in story automatically rendered it an immortal dream would be meaningless, because no one would know that the world could be otherwise. Of course the language that told the story was magical! Of course it was godly! And this, retrospectively, we might call animism. Everything is alive, the signifier of its own godhead.

At first, perhaps, signifiers sprang up naturally as images from the well of dream. But as those signifiers were put to increasingly various use they must have become independent. The abstract was born in the space between the separated signified and signifier. The signifier began to assume increasing importance. With the growth in the complexity of language, time also began to shift and flow. It left behind strata. Elementals of bison, waterfall, hill and tree became gods of polytheistic mythology, who lived through language, and therefore in time, and thus living, died, and became fossils. The sacred became abstract and withdrew to fill the great, unseen emptiness behind the sky. This was monotheism. God and man were as separate as the very words ‘God’ and ‘man’ and the now abstracted, one might say Platonic, meanings they signified. Yet in all this division the sacred did exist. What was important was to exist in the correct syntactical relation to one’s God. Even if all words are separate, as long as they are all in the right place, creation is redeemed; “The snail is on the thorn; God’s in his Heaven – all’s right with the world!” Religion is the syntax that binds one meaning to another, and it is the over-arching narrative that guarantees a happy ending to those words with positive associations (those with negative associations must suffer eternal hell). Religion in this case is story taken literally. The story, though separated from the world by the gulf of abstraction, still retains the authority of the sacred; it is at once a story and life itself. Therefore, to lay down one’s life for the story is to regain that life a thousandfold. The reality of the story reinforces the reality of life, the reality of Earth that of Heaven and, on both counts, vice versa. This life matters because Heaven, too, matters. This life is real because Heaven, too, is real. Stated once more, briefly – the story is real.

Exactly why this form of religion fell I cannot now say, though retrospectively it appears inevitable. Perhaps it was for the same reasons that the polytheistic gods of mythology became fossilised – the natural action of language-quickened time. Or perhaps such an explanation is too vague and glib. Perhaps the newly complex language of religion was torn apart by the intolerable opposites of eternal Heaven and eternal Hell. In any case, it did fall. Not that it disappeared entirely. The great Word-God of religion simply suffered a collapse in which vast chunks of its body were broken and scattered, forming numbers of people who could not agree on the meaning of the words they used or the principles behind them. Those who preached that the story of the Word-God was universal were now preaching a self-evident absurdity. This was the age not of the universal, but of the individual. If I recall correctly, it was called first ‘modernism’ and then ‘post-modernism’, though I am now unsure of the difference between the two. ‘Modernism’, I believe, was basically a transitional period – I suppose all periods are – representing the mourning of mankind for the death of the Word-God and of universality. It was a tragic age. The only stories left to tell were the confessions of godless individuals. Post-modernism was simply life after the tragical catharsis of mourning had passed. The Word-God was dead and his corpse was the breeding ground for countless worms. This was the age of consumerism. Instead of religion there was entertainment.

Perhaps the ultimate symbol of post-modernism is television. If there was no God now to grant us immortality, then we had to attain it by other means. We surrounded ourselves with a glowing forcefield of picture-boxes to keep out death. These were like the mirror that language and story had once been, except that the images they showed were not really our own. Where once religion had made us immortal by rendering both life and after-life equally real, now television made us immortal by rendering everything – life and after-life – equally unreal. Nothing now was real. We sat in front of the picture-box that was television and watched people shoot each other in distant lands on the news while we ate our dinner, and when the news was over we watched actors shoot each other in distant lands, or near. Finally, it made no difference. Television turned the very fabric of life into fiction. If someone died or some terrible disaster took place, it did not matter, because it was all part of a safe, fictional existence made stable by having been recorded, broadcast and watched – thus receiving the redeeming official stamp of the broadcasting corporations.

Of course, there were problems with this form of immortality, too. Reality, in that age, was associated with concrete – the grey substance with which we built our roads and cities. But this association of reality with concrete was precisely the lie by which we tried to trick our way to immortality, just as we tricked ourselves by saying that we ‘fought for peace’. Concrete was, in fact, the very opposite of reality. It was what cut us off from the world, from the very earth beneath us, and from death, since it was designed to create a sterile, insulating safety zone. It was concrete that rendered all things unreal. We had glimpses of this when cracks appeared in the concrete and death came through in violent, gut-churning forms that the drama of television, always dignifying each death and disaster with incidental music, had not prepared us for. We knew when we saw the cracks of violence that the safe immortality of post-modernism was a lie. We knew, and we felt sick.

But perhaps one of the aspects of post-modernism that interests me most as a story-teller, is what has been called ‘the aesthetics of plenty’, but what I would like to call ‘the junction of parallel worlds’.

The beginning of post-modernism, like the beginning of story and time itself, is difficult to pin-point. One possible beginning of many is the movement known as Pop art, which took place at the start of the second half of the twentieth century. In fact, it is in relation to Pop art that the term ‘an aesthetic of plenty’ was commonly used. Some of the best-known practitioners of this art were Eduardo Paolozzi, Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol. In Warhol’s work in particular, we may discern some of the principle mechanisms behind the aesthetic. One work consists simply of the face of screen idol Marilyn Monroe reduplicated many time to form a grid of faces. The idea of plenty is here explicitly associated with the world of fame and the fictions of films. Film – which would become television – is the fountainhead of plenty, since it is a portal to a world whose resources are absolutely inexhaustible. As if to prove this inexhaustibility, Warhol has given us not one Monroe, but many, in a symbolic gesture at infinitude. At the same time, none of these are depictions of the ‘real’ Monroe. They are two-dimensional images whose source is a two-dimensional image. The implication is that there is no original; there are only copies. This is another way of restating my earlier formula – post-modernism gave us immortality by making everything unreal. The inexhaustible ‘plenty’ was another manifestation of immortality’s eternity. Another effect of this reduplication was the destruction of the gap in value between ‘real’ and ‘fake’, ‘original’ and ‘copy’. Perhaps this could be seen as a flat and sterile reflection of animism, in which all things were equally alive and sacred. In Pop art, all things were equally works of art.

Another of Warhol’s works plays the same trick with a can of Campbell’s soup. It is reduplicated in symbolic plenty, in the same way as Monroe’s face. Perhaps the very idea of this reduplication came from seeing cans of soup piled up this way in a supermarket. In any case, viewing the two works next to each other it is easy to draw a parallel between the ‘plenty’ of fame and the ‘plenty’ of mass production and consumerism. This was the mass production that had its inception over a hundred years earlier in Britain’s Industrial Revolution, which one English poet spoke of ominously at the time, naming its manufacturing mills “dark” and “Satanic”.

Warhol’s symbolic gesture in creating these images was to form the template of human culture for over half a century.

In order to describe this aesthetic of plenty with greater clarity, I would like to now name what I believe to be its antithesis – Buddhism. Buddhism was – I do not know for certain whether any adherents survive – a mode of religion that began in India at some time around 500 BC. From there it spread eastward across the continent of Asia until finally it arrived at the Japanese archipelago. One of the forms of Buddhism to emerge in Japan, and perhaps the most famous form in the West – though it was, in fact, based upon the Chan Buddhism of China – was Zen. This was a particularly abstract and ascetic form of the religion and was probably responsible for the minimalism associated with traditional Japanese aesthetics. Where does this minimalism spring from within Buddhist doctrine? All life is suffering. All suffering is caused by desire. Therefore, the only way to overcome suffering is by extinguishing desire. The extinguishing of desire, indeed, of the very self that is the source of desire, is called Nirvana. And how is Nirvana described? It is a state of non-existence, which is, perhaps, as minimalistic as it is possible to be. Non-existence, apparently, is much misunderstood. But since I do not understand it myself, there is little point in trying to explain where the misunderstanding deviates from the truth. Suffice it to say, Nirvana seems to be a form of accepting the world as it is by living completely in the here and now. In that sense, Buddhism is the enemy of both art and consumerism. The artist, after all, is driven by desire. He has a vision of another world, a better world, and he tries to conjure it in his art. Consumerism, likewise, and even more obviously, is based upon desire. Artists and consumers both, are caught in the world of illusory form that the Buddhists called ‘Samsara’. Instead of accepting the world as it is, they are bent on multiplying the forms of Samsara by any means possible. It is intolerable that any idea should be left unrealised, any invention left unmade, any role left unplayed, any story unwritten, any life unlived. They must leave no stone of existence unturned; they must exhaust all possibilities. To do otherwise is, I repeat, intolerable. And thus, at the height of this post-modern aesthetic of plenty, the shelves of supermarkets were filled with a hundred different kinds of toothpaste and shampoo and breakfast cereal, and the television stations bred like a virus, multiplying the mirror of possible realities to shield us against death. This was the spaghetti junction of parallel worlds. But the plenty, it seems, is now past. The junction is behind us. We are on single, narrow roads again.

And that is the story of story so far. It has reached an uncertain stage indeed, but I hope that by writing about it in this way I will affirm its sacred and eternal nature.

Two things occur to me now that I have written this metastory. The first is that the immortalising quality of story might be precisely the reason I cannot seem to write this as if there is no audience. Maybe such a thing is impossible by definition, since a story implies the ultimate audience of ‘a god’. And yet I wish I could write as if there were no audience. Perhaps then, at last, I would break through to reality. Am I, then, still infected by the post-modernism that made all things unreal?

The second thing that occurs to me is that none of this has really answered my greatest and most personal question – If language and story came originally from the wellsprings of the sacred in the real world, why is it that I feel my soul is in story, but nowhere in the life I have lived in this world? I seem to be saying that my soul alone is different and precious, that my soul is a world that never existed. Is that possible? It’s like saying that the ultimate god (or the ultimate truth) is an outsider with no home in existence. Or that the ultimate god is a single damned individual. But yes, that is how I feel.

A single damned individual.

Blog Resumed

I originally started this blog as a kind of back-up copy of my main blog. However, through laziness, inertia and so on, I began to get behind in backing up, and eventually, the task of catching up with the backlog just seemed too great. So I have decided not to catch up, but to forget all the intervening blog posts I haven't backed up here, and start afresh, backing up all posts as of today. Any questions?

I originally started this blog as a kind of back-up copy of my main blog. However, through laziness, inertia and so on, I began to get behind in backing up, and eventually, the task of catching up with the backlog just seemed too great. So I have decided not to catch up, but to forget all the intervening blog posts I haven't backed up here, and start afresh, backing up all posts as of today. Any questions?