Links

- STOP ESSO

- The One and Only Bumbishop

- Hertzan Chimera's Blog

- Strange Attractor

- Wishful Thinking

- The Momus Website

- Horror Quarterly

- Fractal Domains

- .alfie.'s Blog

- Maria's Fractal Gallery

- Roy Orbison in Cling Film

- Iraq Body Count

- Undo Global Warming

- Bettie Page - We're Not Worthy!

- For the Discerning Gentleman

- All You Ever Wanted to Know About Cephalopods

- The Greatest Band that Never Were - The Dead Bell

- The Heart of Things

- Weed, Wine and Caffeine

- Division Day

- Signs of the Times

Archives

- 05/01/2004 - 06/01/2004

- 06/01/2004 - 07/01/2004

- 07/01/2004 - 08/01/2004

- 08/01/2004 - 09/01/2004

- 09/01/2004 - 10/01/2004

- 10/01/2004 - 11/01/2004

- 11/01/2004 - 12/01/2004

- 12/01/2004 - 01/01/2005

- 01/01/2005 - 02/01/2005

- 02/01/2005 - 03/01/2005

- 03/01/2005 - 04/01/2005

- 05/01/2005 - 06/01/2005

- 06/01/2005 - 07/01/2005

- 07/01/2005 - 08/01/2005

- 08/01/2005 - 09/01/2005

- 09/01/2005 - 10/01/2005

- 10/01/2005 - 11/01/2005

- 11/01/2005 - 12/01/2005

- 12/01/2005 - 01/01/2006

- 01/01/2006 - 02/01/2006

- 02/01/2006 - 03/01/2006

- 09/01/2006 - 10/01/2006

- 10/01/2006 - 11/01/2006

- 11/01/2006 - 12/01/2006

- 12/01/2006 - 01/01/2007

- 01/01/2007 - 02/01/2007

- 02/01/2007 - 03/01/2007

- 03/01/2007 - 04/01/2007

- 04/01/2007 - 05/01/2007

- 05/01/2007 - 06/01/2007

- 06/01/2007 - 07/01/2007

- 07/01/2007 - 08/01/2007

- 08/01/2007 - 09/01/2007

- 09/01/2007 - 10/01/2007

- 10/01/2007 - 11/01/2007

- 11/01/2007 - 12/01/2007

- 12/01/2007 - 01/01/2008

- 01/01/2008 - 02/01/2008

- 02/01/2008 - 03/01/2008

- 03/01/2008 - 04/01/2008

- 04/01/2008 - 05/01/2008

- 07/01/2008 - 08/01/2008

Being an Archive of the Obscure Neural Firings Burning Down the Jelly-Pink Cobwebbed Library of Doom that is The Mind of Quentin S. Crisp

Tuesday, August 31, 2004

If You Were a Dog

I spotted a link to a quiz on .alfie.'s blog which claims to divine which common breed of dog you would be if you were a dog by analysing your answers to a few questions. I'm not sure of its scientific accuracy, but here was my result:

Should you be interested, the link is here.

Actually, I do think mine is quite accurate, apart from the 'fearless in the face of the enemy' bit. Uncanny!

I spotted a link to a quiz on .alfie.'s blog which claims to divine which common breed of dog you would be if you were a dog by analysing your answers to a few questions. I'm not sure of its scientific accuracy, but here was my result:

Should you be interested, the link is here.

Actually, I do think mine is quite accurate, apart from the 'fearless in the face of the enemy' bit. Uncanny!

Monday, August 30, 2004

Quentin Crisp/Quentin S Crisp – Who Do I Think I Am?

I wanted to see if I’m famous yet – ha ha! – so I looked up my name on Google. Well, there are a few entries there. It is interesting to find one’s name in unexpected places. One entry was a kind of catalogue listing a number of small press publishers and giving information on their releases. In an entry on an anthology containing one of my stories was contained the following quote: “Any collection with a story by Quentin Crisp is worth having for eclecticism alone.” I was quite pleased with myself. Someone’s been following my progress and decided that my work is not only eclectic, but worth seeking out, I thought to myself. Then I noticed another entry, about a short story collection to which I had written the introduction. “Interesting to see an introduction provided by the best-selling author Quentin Crisp, who usually does not stray into the realm of genre fiction,” ran the quote. I don’t know if that’s verbatim. Great! I thought. I’m a fricking best-selling author and I didn’t even know it! I’ll have to get on the phone to someone or other and check out how I can collect the royalties I didn’t know I had… and so on. But what does he mean, “usually does not stray into the realm of genre fiction”? Surely I’ve done a fair bit of straying in that area? And then it dawned on me – whoever wrote this thinks I’m the OTHER Quentin Crisp. Let’s try and clear up this confusion, shall we?

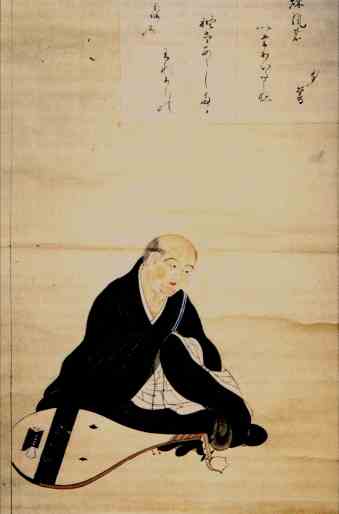

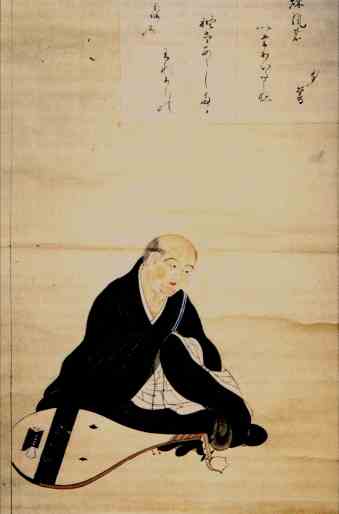

Here is a picture of the other Quentin Crisp:

Now, here is a picture of me:

I’ve just been interrupted by my friend Ross, where was I? Oh yes, this is me, the one without the heavy make-up.

Yes, you may be wondering, but which one is the REAL Quentin Crisp? Well, I’m quite fond of the other one, but now that it’s me against him I have to be merciless and say, I am the real Quentin Crisp. How can I say that with such certainty? Well, there’s a rather boring explanation. I was christened Quentin Crisp. He was christened Dennis Pratt. It’s that simple. Ah, you might say, but what’s in a name? He is the real Quentin Crisp in the sense that he is the famous and therefore the definite article. Hmmm. I wonder. I have suffered for my name in the playground and in adult life. I routinely carry my passport around with me, and, when people refuse to believe my name, which is a frequent occurrence, I show them. While Dennis may have suffered for many things, I don’t think he suffered for his name. I think I have earned my name.

So you’re the real Quentin Crisp, then? Well, what does that mean? Who do you think you are? This is the kind of question that I feel I will have to face a number of times before I die. Strangely, I do have quite a distinct idea of who I am, though it’s not an idea that is easy to put into words. I say ‘strangely’ because, these days it’s practically a heresy for any intellectual to suggest that there is such a thing as a self. I, on the other hand, for better or for worse, am very attached to the self and to individual identity. That attachment to individual identity is…er ….very much a part of my identity. That is why, even though, for years and years, to this very day, I hate and detest introductions, because I will have to give my name to someone, when it came to trying to make up a pen name with which to write, I just could not do it. I could not think of anything apart from the name I have. I identify with my literal identity. That’s the kind of guy I am, and I no longer expect anyone to understand that.

Quentin Crisp – it’s hardly a common name, is it? It would have been the perfect symbol of my individuality if only it had not already been identified with a famous person. Now, instead of individuality, it must be the symbol of a kind of irony, a kind of destiny that is not destiny. And that irony is further increased by that fact that my predecessor changed his name to mine. I kept mine the same, but now it looks as if I am the one following in his footsteps. Anyway, you can tell us apart because I use my middle initial, S, as my official pen name.

I suppose you want to know if I’m gay, now, too? For the answer to that question you’ll have to read my works – especially The Haunted Bicycle, which should be out soon-ish – and try and work it out for yourself. So there.

I wanted to see if I’m famous yet – ha ha! – so I looked up my name on Google. Well, there are a few entries there. It is interesting to find one’s name in unexpected places. One entry was a kind of catalogue listing a number of small press publishers and giving information on their releases. In an entry on an anthology containing one of my stories was contained the following quote: “Any collection with a story by Quentin Crisp is worth having for eclecticism alone.” I was quite pleased with myself. Someone’s been following my progress and decided that my work is not only eclectic, but worth seeking out, I thought to myself. Then I noticed another entry, about a short story collection to which I had written the introduction. “Interesting to see an introduction provided by the best-selling author Quentin Crisp, who usually does not stray into the realm of genre fiction,” ran the quote. I don’t know if that’s verbatim. Great! I thought. I’m a fricking best-selling author and I didn’t even know it! I’ll have to get on the phone to someone or other and check out how I can collect the royalties I didn’t know I had… and so on. But what does he mean, “usually does not stray into the realm of genre fiction”? Surely I’ve done a fair bit of straying in that area? And then it dawned on me – whoever wrote this thinks I’m the OTHER Quentin Crisp. Let’s try and clear up this confusion, shall we?

Here is a picture of the other Quentin Crisp:

Now, here is a picture of me:

I’ve just been interrupted by my friend Ross, where was I? Oh yes, this is me, the one without the heavy make-up.

Yes, you may be wondering, but which one is the REAL Quentin Crisp? Well, I’m quite fond of the other one, but now that it’s me against him I have to be merciless and say, I am the real Quentin Crisp. How can I say that with such certainty? Well, there’s a rather boring explanation. I was christened Quentin Crisp. He was christened Dennis Pratt. It’s that simple. Ah, you might say, but what’s in a name? He is the real Quentin Crisp in the sense that he is the famous and therefore the definite article. Hmmm. I wonder. I have suffered for my name in the playground and in adult life. I routinely carry my passport around with me, and, when people refuse to believe my name, which is a frequent occurrence, I show them. While Dennis may have suffered for many things, I don’t think he suffered for his name. I think I have earned my name.

So you’re the real Quentin Crisp, then? Well, what does that mean? Who do you think you are? This is the kind of question that I feel I will have to face a number of times before I die. Strangely, I do have quite a distinct idea of who I am, though it’s not an idea that is easy to put into words. I say ‘strangely’ because, these days it’s practically a heresy for any intellectual to suggest that there is such a thing as a self. I, on the other hand, for better or for worse, am very attached to the self and to individual identity. That attachment to individual identity is…er ….very much a part of my identity. That is why, even though, for years and years, to this very day, I hate and detest introductions, because I will have to give my name to someone, when it came to trying to make up a pen name with which to write, I just could not do it. I could not think of anything apart from the name I have. I identify with my literal identity. That’s the kind of guy I am, and I no longer expect anyone to understand that.

Quentin Crisp – it’s hardly a common name, is it? It would have been the perfect symbol of my individuality if only it had not already been identified with a famous person. Now, instead of individuality, it must be the symbol of a kind of irony, a kind of destiny that is not destiny. And that irony is further increased by that fact that my predecessor changed his name to mine. I kept mine the same, but now it looks as if I am the one following in his footsteps. Anyway, you can tell us apart because I use my middle initial, S, as my official pen name.

I suppose you want to know if I’m gay, now, too? For the answer to that question you’ll have to read my works – especially The Haunted Bicycle, which should be out soon-ish – and try and work it out for yourself. So there.

Saturday, August 28, 2004

The Second Most Important Thing in Life

I’m rather tired of people who can only be clever, and am beginning to deplore my own attempts to be clever. My interactions with other human beings leave me feeling frustrated and, well, actually, sometimes quite furious. There’s a line from a Morrissey song that goes, “You fight with your right hand/ And caress with your left hand/ Everyone I know is sick to death of you.” Well, I do feel very much as if I blow hot and cold, so to speak, fight with my right hand and caress with my left hand. And I do tend to hate myself for it and feel that other people must hate me for it, too. But, you know, I’m dying of loneliness. That’s all.

Some years ago, a friend of mine told me a quote that he claimed was from Oscar Wilde. I’ve never actually come across the quote in any other context, so I can’t be certain of the truth. However, the quote has stayed with me, and has actually come to haunt me more and more in recent times. The quote goes like this: “There are only two important things in life. The first is that everyone must act as superficially as possible. No one has yet discovered the second.”

It seems to me that the implications of this quote are clear. The second most important thing is clearly the reason why we are all here, and the reason no one has ever discovered it is because they are all too busy following the first ‘most important thing in life’. But I have always, always, always been one of those shameful, embarrassing, annoying, selfish, unwelcome, deluded people who burn to discover the second ‘most important thing in life’. And because of this desire I have frequently got into trouble with people. I reach out, and I am disappointed.

It seems to me that people don’t really want to know each other. It is important to be independent, to stand on your own two feet, not to bother anyone. And if you show signs of actually needing other people, of not standing on your own two feet, people find this a dreadful nuisance. Somehow they have learnt to be entirely self-contained. It is a terrible crime to be any other way. In fact, just as human beings wear clothes to cover up the crime of their naked bodies, they adopt social superficiality to cover up a nakedness of the soul which is considered to be a thousand times more obscene than that of the body. Why? What is obscene about the human soul? I would say that, if there is something obscene about it, it is that we have already lived for generations and generations upon lies. We clothe ourselves in lies. We eat lies. We build and shelter in lies. We sleep in lies. We bathe in lies. We buy and sell lies. Anything that reminds us of these lies is ugly in the extreme.

And so to heterosexuality. Of course, people cannot maintain this condition of being self-contained forever. So what do they do? The only release that is possible in this society is through sex or ‘romantic love’. One thing I hate about heterosexuality is that it makes love something exclusive. Once someone finds themselves in a relationship it’s, “I’m all right, Jack!” There is one person that is important in their life, one person only. To hell with the rest of them! “When I am with you I can be myself!” they say. Once they leave the presence of that person they enter the wasteland where by law everyone must act in the most superficial way possible. Under such pressure to contain the entire meaning of life, when no meaning is to be found elsewhere because people are afraid of investing meaning in anything else, such relationships very often fall to pieces and end in heartbreak.

And for people like me? Sad people, yes. People who should ‘get a life’, yes. Since we do not have that one special person, we demand meaning from other areas of our life, such as friendships. And in so doing we annoy people. And in so doing we become frustrated and angry and bitter.

But what if, what if that second ‘most important thing in life’ were actually discovered? What it would require would be that people stopped being so self-contained and actually decided to take an interest in people APART FROM THEIR SEXUAL PARTNERS. We might find that in valuing other people we were able to build a world where there was no want. I realise that people tend to recoil from such ‘peace and love’ Utopianism these days. But we’re at a point in history where, if we don’t have Utopia, what we will have very soon is Hell or extinction.

I’m not claiming to know everything. I myself don’t know exactly how to discover that second ‘most important thing’. I try, and I meet with no co-operation, and in fear I retreat again. Perhaps I’m sacred too, that in the end I would find that there was no second ‘most important thing’ and that we’re all nothing but empty shells. On that subject, I can’t help thinking of a song by The Cure, based on a short story by Charles Baudelaire. The lyrics are as follows:

How Beautiful You Are!

You want to know why I hate you?

Well I'll try and explain...

You remember that day in Paris

When we wandered through the rain

And promised to each other

That we'd always think the same

And dreamed that dream

To be two souls as one

And stopped just as the sun set

And waited for the night

Outside a glittering building

Of glittering glass and burning light...

And in the road before us

Stood a weary greyish man

Who held a child upon his back

A small boy by the hand

The three of them were dressed in rags

And thinner than the air

And all six eyes stared fixedly on you

The father's eyes said "Beautiful!

How beautiful you are!"

The boy's eyes said

"How beautiful!

She shimmers like a star!"

The child’s eyes uttered nothing

But a mute and utter joy

And filled my heart with shame for us

At the way we are

I turned to look at you

To read my thoughts upon your face

And gazed so deep into your eyes

So beautiful and strange

Until you spoke

And showed me understanding is a dream

"I hate these people staring

Make them go away from me!"

The father’s eyes said "Beautiful!

How beautiful you are!"

The boy’s eyes said

"How beautiful! She glitters like a star!"

The child's eyes uttered joy

And stilled my heart with sadness

For the way we are

And this is why I hate you

And how I understand

That no-one ever knows or loves another

Or loves another

Perhaps it is impossible actually even to meet another person. God knows I feel as if I’ve never met anyone even for a single moment. I have tried. I really have tried. And now I am reminded of a poem by Mervyn Peake:

Is There no Love Can Link Us?

Is there no thread to bind us-I and he

Who is dying now, this instant as I write

And may be cold before this line's complete?

And is there no power to link us-I and she

Across whose body the loud roof is falling?

Or the child, whose blackening skin

Blossoms with hideous roses in the smoke?

Is there no love can link us -I and they?

Only this hectic moment? This fierce instant

Striking now

Its universal, its uneven blow?

There is no other link. Only this sliding

Second we share: this desperate edge of now.

I have tried. Do other people try? I sometimes wonder. Is there anybody out there? Will I ever actually meet another human being? Will we discover what that second ‘most important thing’ is before our superficiality drowns and chokes the whole planet with the pollution of lies?

I’m rather tired of people who can only be clever, and am beginning to deplore my own attempts to be clever. My interactions with other human beings leave me feeling frustrated and, well, actually, sometimes quite furious. There’s a line from a Morrissey song that goes, “You fight with your right hand/ And caress with your left hand/ Everyone I know is sick to death of you.” Well, I do feel very much as if I blow hot and cold, so to speak, fight with my right hand and caress with my left hand. And I do tend to hate myself for it and feel that other people must hate me for it, too. But, you know, I’m dying of loneliness. That’s all.

Some years ago, a friend of mine told me a quote that he claimed was from Oscar Wilde. I’ve never actually come across the quote in any other context, so I can’t be certain of the truth. However, the quote has stayed with me, and has actually come to haunt me more and more in recent times. The quote goes like this: “There are only two important things in life. The first is that everyone must act as superficially as possible. No one has yet discovered the second.”

It seems to me that the implications of this quote are clear. The second most important thing is clearly the reason why we are all here, and the reason no one has ever discovered it is because they are all too busy following the first ‘most important thing in life’. But I have always, always, always been one of those shameful, embarrassing, annoying, selfish, unwelcome, deluded people who burn to discover the second ‘most important thing in life’. And because of this desire I have frequently got into trouble with people. I reach out, and I am disappointed.

It seems to me that people don’t really want to know each other. It is important to be independent, to stand on your own two feet, not to bother anyone. And if you show signs of actually needing other people, of not standing on your own two feet, people find this a dreadful nuisance. Somehow they have learnt to be entirely self-contained. It is a terrible crime to be any other way. In fact, just as human beings wear clothes to cover up the crime of their naked bodies, they adopt social superficiality to cover up a nakedness of the soul which is considered to be a thousand times more obscene than that of the body. Why? What is obscene about the human soul? I would say that, if there is something obscene about it, it is that we have already lived for generations and generations upon lies. We clothe ourselves in lies. We eat lies. We build and shelter in lies. We sleep in lies. We bathe in lies. We buy and sell lies. Anything that reminds us of these lies is ugly in the extreme.

And so to heterosexuality. Of course, people cannot maintain this condition of being self-contained forever. So what do they do? The only release that is possible in this society is through sex or ‘romantic love’. One thing I hate about heterosexuality is that it makes love something exclusive. Once someone finds themselves in a relationship it’s, “I’m all right, Jack!” There is one person that is important in their life, one person only. To hell with the rest of them! “When I am with you I can be myself!” they say. Once they leave the presence of that person they enter the wasteland where by law everyone must act in the most superficial way possible. Under such pressure to contain the entire meaning of life, when no meaning is to be found elsewhere because people are afraid of investing meaning in anything else, such relationships very often fall to pieces and end in heartbreak.

And for people like me? Sad people, yes. People who should ‘get a life’, yes. Since we do not have that one special person, we demand meaning from other areas of our life, such as friendships. And in so doing we annoy people. And in so doing we become frustrated and angry and bitter.

But what if, what if that second ‘most important thing in life’ were actually discovered? What it would require would be that people stopped being so self-contained and actually decided to take an interest in people APART FROM THEIR SEXUAL PARTNERS. We might find that in valuing other people we were able to build a world where there was no want. I realise that people tend to recoil from such ‘peace and love’ Utopianism these days. But we’re at a point in history where, if we don’t have Utopia, what we will have very soon is Hell or extinction.

I’m not claiming to know everything. I myself don’t know exactly how to discover that second ‘most important thing’. I try, and I meet with no co-operation, and in fear I retreat again. Perhaps I’m sacred too, that in the end I would find that there was no second ‘most important thing’ and that we’re all nothing but empty shells. On that subject, I can’t help thinking of a song by The Cure, based on a short story by Charles Baudelaire. The lyrics are as follows:

How Beautiful You Are!

You want to know why I hate you?

Well I'll try and explain...

You remember that day in Paris

When we wandered through the rain

And promised to each other

That we'd always think the same

And dreamed that dream

To be two souls as one

And stopped just as the sun set

And waited for the night

Outside a glittering building

Of glittering glass and burning light...

And in the road before us

Stood a weary greyish man

Who held a child upon his back

A small boy by the hand

The three of them were dressed in rags

And thinner than the air

And all six eyes stared fixedly on you

The father's eyes said "Beautiful!

How beautiful you are!"

The boy's eyes said

"How beautiful!

She shimmers like a star!"

The child’s eyes uttered nothing

But a mute and utter joy

And filled my heart with shame for us

At the way we are

I turned to look at you

To read my thoughts upon your face

And gazed so deep into your eyes

So beautiful and strange

Until you spoke

And showed me understanding is a dream

"I hate these people staring

Make them go away from me!"

The father’s eyes said "Beautiful!

How beautiful you are!"

The boy’s eyes said

"How beautiful! She glitters like a star!"

The child's eyes uttered joy

And stilled my heart with sadness

For the way we are

And this is why I hate you

And how I understand

That no-one ever knows or loves another

Or loves another

Perhaps it is impossible actually even to meet another person. God knows I feel as if I’ve never met anyone even for a single moment. I have tried. I really have tried. And now I am reminded of a poem by Mervyn Peake:

Is There no Love Can Link Us?

Is there no thread to bind us-I and he

Who is dying now, this instant as I write

And may be cold before this line's complete?

And is there no power to link us-I and she

Across whose body the loud roof is falling?

Or the child, whose blackening skin

Blossoms with hideous roses in the smoke?

Is there no love can link us -I and they?

Only this hectic moment? This fierce instant

Striking now

Its universal, its uneven blow?

There is no other link. Only this sliding

Second we share: this desperate edge of now.

I have tried. Do other people try? I sometimes wonder. Is there anybody out there? Will I ever actually meet another human being? Will we discover what that second ‘most important thing’ is before our superficiality drowns and chokes the whole planet with the pollution of lies?

Sunday, August 22, 2004

Nagai Kafu – Who He?

Well, it’s Sunday, and I asked myself if, for once, I might forget about my onerous duties as a writer and just relax a bit. I haven’t really done that so far today, but if I get a little time after writing this entry in my blog, I know the perfect person with whom to relax. That person is Nagai Kafu.

Nagai Kafu is one of my favourite writers. I have yet to meet another human being who counts Kafu as one of their favourite writers, which is a fact both gratifying and rather lonely. At present I am re-reading Mishima’s The Decay of the Angel in the original, and it has occurred to me frequently just how strongly influenced I have been by Mishima in my own writing. But, since few people actually read Mishima, no one seems to notice this influence. It’s there clear as day, mind you.

I have been similarly influenced by Kafu, but if I were to try and pin down that influence in my work, it would be rather a difficult matter. That is perhaps because Kafu himself is so hard to pin down as a writer. What exactly is it that forms his appeal? I do not know if I can answer that question, but I hope I can give a hint or two here.

Kafu is, to me, the gentleman of leisure par excellence. Kafu (nee Sokichi) was born in 1879 in the Koishikawa district of Tokyo. His family was well to do – his father being a high-ranking bureaucrat – but Kafu was of a rebellious nature. From an early age he began to frequent such quarters of the city as were the haunts of actors, artists, geisha and all other such denizens of the demimonde that were execrated by the Confucian values of his family. In the year 1899, at the age of twenty, his first story, ‘Misty Night’ was published, and, in secret he apprenticed himself to a professional storyteller, or ‘rakugoka’. Rakugo is the Japanese art of reciting comic monologues. The next year, also in secret, he apprenticed himself to a playwright at the Kabuki Theatre. Thus he became steeped in the elegant dissipations and shadowy arts of the Edo Period.

In 1903, however, Kafu was sent to the United States of America. His father, apparently, hoped that an American education might do something for his wayward son. During his four years in America he gathered together the material that was to become Tales of America. His experiences there, as one of the first Japanese to travel to the West, gave him something of the cosmopolitan taste lacking in his contemporaries. Being a devotee of French literature, Kafu made sure he did not return directly to Japan, but came back via France, where he spent, against his father’s wishes, almost a year. There he composed his Tales of France, which were banned upon publication, because of certain sections that were deemed to be liable to corrupt the public morals.

Well, you’re probably beginning to get the picture by now. Think elegance and decadence and you can’t go too far wrong. Of course, I have no intention of writing a detailed biography here, only to offer a few stray thoughts.

If Mishima’s prose is as vivid and brilliant as the colours of a Chinese temple, Kafu’s prose reminds me instead of sunlight shining through the paper panels of a Japanese sliding door. It seems gentle, subdued and monotonous, with a certain sadness about it. But what at first seems a monotone reveals itself gradually as something sophisticated and multi-layered, with a mysterious flavour that lingers stronger and stronger after the first taste.

When I think of Kafu, I think of the Japanese word ‘shibui’. The fact is, I am still not sure of the meaning of this word, and no matter how many times it is explained to me, I still cannot say with confidence that I understand. But I have an impression of it’s meaning, and to give that impression substance, I refer to Kafu. Shibui refers to taste in art and in general, which is not obvious and brightly coloured, but is somewhat more restrained. It is often a word that is associated with an older generation. If a young person is called shibui, it is usually because their taste is like that of someone older than they. I like to think of it as ‘geezer cool’. Take an old geezer, make him unfeasibly elegant and cool, and there you have a personification of ‘shibui’ – IE Nagai Kafu.

When I write, I have a ritual to get me in the right mood. That ritual involves the brewing of green tea with a delicate little tea set I purchased in a teashop near Kyoto. As I pour the boiling water into the vessel for cooling the water, then, after some minutes, pour it into the ‘houhin’ where the green leaves of tea are nestled, and replace the lid, waiting for it to steep, I like to imagine that Kafu might have had a similar ritual as he sat before his ink-stone. In all forms of elegant leisure, and especially those either decadent or literary, I seem to sense the ghost of Kafu.

I have a favourite photograph of Kafu. I don’t expect I’ll be able to find it on the Internet. It shows Kafu quite late on in his life, though I don’t know exactly how old he is in the photo. He is kneeling on the floor in traditional Japanese style, though he is wearing a western suit. His shirt is unbuttoned at the neck, and there is no tie. His glasses are round and black-framed. He is smiling broadly, and exposing a gap in his front teeth where two or three teeth are missing. What I love about this photo is the fact that he so clearly does not give a damn about his missing teeth. That’s hard to imagine in this age of Hollywood actors for whom capped teeth are more or less mandatory (I remember how upset I was when Bowie sacrificed his wonderfully crooked teeth to this trend). Anyway, I look at this photo of Kafu, and, though my understanding of the word ‘shibui’ is not great enough for me to use it with confidence here, I think to myself, now, there’s a geezer!

Well, it’s Sunday, and I asked myself if, for once, I might forget about my onerous duties as a writer and just relax a bit. I haven’t really done that so far today, but if I get a little time after writing this entry in my blog, I know the perfect person with whom to relax. That person is Nagai Kafu.

Nagai Kafu is one of my favourite writers. I have yet to meet another human being who counts Kafu as one of their favourite writers, which is a fact both gratifying and rather lonely. At present I am re-reading Mishima’s The Decay of the Angel in the original, and it has occurred to me frequently just how strongly influenced I have been by Mishima in my own writing. But, since few people actually read Mishima, no one seems to notice this influence. It’s there clear as day, mind you.

I have been similarly influenced by Kafu, but if I were to try and pin down that influence in my work, it would be rather a difficult matter. That is perhaps because Kafu himself is so hard to pin down as a writer. What exactly is it that forms his appeal? I do not know if I can answer that question, but I hope I can give a hint or two here.

Kafu is, to me, the gentleman of leisure par excellence. Kafu (nee Sokichi) was born in 1879 in the Koishikawa district of Tokyo. His family was well to do – his father being a high-ranking bureaucrat – but Kafu was of a rebellious nature. From an early age he began to frequent such quarters of the city as were the haunts of actors, artists, geisha and all other such denizens of the demimonde that were execrated by the Confucian values of his family. In the year 1899, at the age of twenty, his first story, ‘Misty Night’ was published, and, in secret he apprenticed himself to a professional storyteller, or ‘rakugoka’. Rakugo is the Japanese art of reciting comic monologues. The next year, also in secret, he apprenticed himself to a playwright at the Kabuki Theatre. Thus he became steeped in the elegant dissipations and shadowy arts of the Edo Period.

In 1903, however, Kafu was sent to the United States of America. His father, apparently, hoped that an American education might do something for his wayward son. During his four years in America he gathered together the material that was to become Tales of America. His experiences there, as one of the first Japanese to travel to the West, gave him something of the cosmopolitan taste lacking in his contemporaries. Being a devotee of French literature, Kafu made sure he did not return directly to Japan, but came back via France, where he spent, against his father’s wishes, almost a year. There he composed his Tales of France, which were banned upon publication, because of certain sections that were deemed to be liable to corrupt the public morals.

Well, you’re probably beginning to get the picture by now. Think elegance and decadence and you can’t go too far wrong. Of course, I have no intention of writing a detailed biography here, only to offer a few stray thoughts.

If Mishima’s prose is as vivid and brilliant as the colours of a Chinese temple, Kafu’s prose reminds me instead of sunlight shining through the paper panels of a Japanese sliding door. It seems gentle, subdued and monotonous, with a certain sadness about it. But what at first seems a monotone reveals itself gradually as something sophisticated and multi-layered, with a mysterious flavour that lingers stronger and stronger after the first taste.

When I think of Kafu, I think of the Japanese word ‘shibui’. The fact is, I am still not sure of the meaning of this word, and no matter how many times it is explained to me, I still cannot say with confidence that I understand. But I have an impression of it’s meaning, and to give that impression substance, I refer to Kafu. Shibui refers to taste in art and in general, which is not obvious and brightly coloured, but is somewhat more restrained. It is often a word that is associated with an older generation. If a young person is called shibui, it is usually because their taste is like that of someone older than they. I like to think of it as ‘geezer cool’. Take an old geezer, make him unfeasibly elegant and cool, and there you have a personification of ‘shibui’ – IE Nagai Kafu.

When I write, I have a ritual to get me in the right mood. That ritual involves the brewing of green tea with a delicate little tea set I purchased in a teashop near Kyoto. As I pour the boiling water into the vessel for cooling the water, then, after some minutes, pour it into the ‘houhin’ where the green leaves of tea are nestled, and replace the lid, waiting for it to steep, I like to imagine that Kafu might have had a similar ritual as he sat before his ink-stone. In all forms of elegant leisure, and especially those either decadent or literary, I seem to sense the ghost of Kafu.

I have a favourite photograph of Kafu. I don’t expect I’ll be able to find it on the Internet. It shows Kafu quite late on in his life, though I don’t know exactly how old he is in the photo. He is kneeling on the floor in traditional Japanese style, though he is wearing a western suit. His shirt is unbuttoned at the neck, and there is no tie. His glasses are round and black-framed. He is smiling broadly, and exposing a gap in his front teeth where two or three teeth are missing. What I love about this photo is the fact that he so clearly does not give a damn about his missing teeth. That’s hard to imagine in this age of Hollywood actors for whom capped teeth are more or less mandatory (I remember how upset I was when Bowie sacrificed his wonderfully crooked teeth to this trend). Anyway, I look at this photo of Kafu, and, though my understanding of the word ‘shibui’ is not great enough for me to use it with confidence here, I think to myself, now, there’s a geezer!

Tuesday, August 17, 2004

Acknowledgement

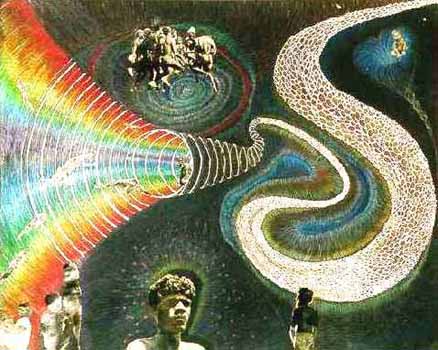

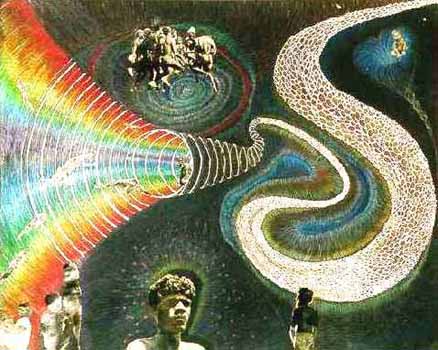

Whilst surfing the net, I discovered the site of one of the artists from whom I borrowed an image ealier in my blog. The image was Neural Pathways, and a very nice piece of work it is, too. All the images in my blog are borrowed, and, whilst it is easy to trace their source by holding the cursor over them, I would like to give more specific credit when I have the time and oppotunity, so please do check out the site of JD Franklin, the creator of Neural Pathways.

Whilst surfing the net, I discovered the site of one of the artists from whom I borrowed an image ealier in my blog. The image was Neural Pathways, and a very nice piece of work it is, too. All the images in my blog are borrowed, and, whilst it is easy to trace their source by holding the cursor over them, I would like to give more specific credit when I have the time and oppotunity, so please do check out the site of JD Franklin, the creator of Neural Pathways.

All Things Must Pass

Anyone who knows me will know that I have a great interest in literature generally, and in Japanese literature in particular. I write my own stories, essays and so on, but I am also interested in translating Japanese literature and introducing it to a Western audience. For instance, at the moment, when I have time, which is not often, I am trying to translate Nagai Kafu’s Dwarf Bamboo into English. I have written to a number of professors whom I know to be interested in Kafu or in Japanese literature, to ask for advice in the best way to bring my translation to a public audience, but most of the time I have not even had replies. It seems these professors have better things to do than worry about the promotion of Japanese literature. I even discovered an association dedicated to translated Japanese literature in English, and wrote to them explaining I had studied Japanese literature at Kyoto University and so on, and that I’d love to assist in introducing it to a Western audience. I got no reply.

I don’t know exactly what’s going on here, but I am left with the taste of snobbery and clique-ism in my mouth from such encounters, or non-encounters. Probably I need the right introductions and so on. To me this kind of academic clique-ism is not what literature is about. In fact, it is the very opposite of what literature is about. So, I continue in my own way. Here I would like to present the opening section from a work of classical Japanese literature. The work is called Houjouki, or A Record of my Hut. I don’t have all the information at my fingertips right now, but I believe it was written in the twelfth century. It is a discursive work by a character called Kamo no Choumei, who ended his days as a hermit living in a kind of portable hut of his own devising. The work details certain experiences that Choumei had which led him to the – very Buddhist – realisation that all things pass. These experiences were a series of catastrophes which struck the capital of the day. Of course, I feel that such a work might be appropriate for our own times, when the world as we have known it since the industrial revolution is on the point of collapse.

I don’t suppose that Choumei gave a hoot about things such as copyright, but of course, the work is long out of copyright by now, if it was ever in copyright. I present it here freely in my own translation – which I may try to improve on if I get a moment here and there – in the free spirit that literature should be created and disseminated, and a pox on petty professors and publishers (This doesn’t mean I don’t have to try and make a living with my own works, I might add. Heigh ho!):

The current of the river flows unceasing, and the water, ever-changing, is not that which flowed here first. In the backwaters, bubbles wink out and bubbles appear, but never have they been known to remain for long. And thus too the people of this world and the places in which they dwell.

In the resplendent capital, the dwellings of the mighty and the low line up their roof-ridges, their tiles vying for height. It seems that they have spanned the generations, that they stand eternal, but enquire and you will find the houses that stood of old are all too rare. Perhaps they burned down last year, and in their place, another building. Perhaps what was a great house has crumbled away, and now a small house stands there. And those that dwell within the buildings are also thus. The place is the same, and the people here are many, but of the people I knew of old perhaps only one or two remain in twenty or thirty. This morning someone dies, this evening someone is born. Thus are human lives nothing more than bubbles in a stream.

Anyone who knows me will know that I have a great interest in literature generally, and in Japanese literature in particular. I write my own stories, essays and so on, but I am also interested in translating Japanese literature and introducing it to a Western audience. For instance, at the moment, when I have time, which is not often, I am trying to translate Nagai Kafu’s Dwarf Bamboo into English. I have written to a number of professors whom I know to be interested in Kafu or in Japanese literature, to ask for advice in the best way to bring my translation to a public audience, but most of the time I have not even had replies. It seems these professors have better things to do than worry about the promotion of Japanese literature. I even discovered an association dedicated to translated Japanese literature in English, and wrote to them explaining I had studied Japanese literature at Kyoto University and so on, and that I’d love to assist in introducing it to a Western audience. I got no reply.

I don’t know exactly what’s going on here, but I am left with the taste of snobbery and clique-ism in my mouth from such encounters, or non-encounters. Probably I need the right introductions and so on. To me this kind of academic clique-ism is not what literature is about. In fact, it is the very opposite of what literature is about. So, I continue in my own way. Here I would like to present the opening section from a work of classical Japanese literature. The work is called Houjouki, or A Record of my Hut. I don’t have all the information at my fingertips right now, but I believe it was written in the twelfth century. It is a discursive work by a character called Kamo no Choumei, who ended his days as a hermit living in a kind of portable hut of his own devising. The work details certain experiences that Choumei had which led him to the – very Buddhist – realisation that all things pass. These experiences were a series of catastrophes which struck the capital of the day. Of course, I feel that such a work might be appropriate for our own times, when the world as we have known it since the industrial revolution is on the point of collapse.

I don’t suppose that Choumei gave a hoot about things such as copyright, but of course, the work is long out of copyright by now, if it was ever in copyright. I present it here freely in my own translation – which I may try to improve on if I get a moment here and there – in the free spirit that literature should be created and disseminated, and a pox on petty professors and publishers (This doesn’t mean I don’t have to try and make a living with my own works, I might add. Heigh ho!):

The current of the river flows unceasing, and the water, ever-changing, is not that which flowed here first. In the backwaters, bubbles wink out and bubbles appear, but never have they been known to remain for long. And thus too the people of this world and the places in which they dwell.

In the resplendent capital, the dwellings of the mighty and the low line up their roof-ridges, their tiles vying for height. It seems that they have spanned the generations, that they stand eternal, but enquire and you will find the houses that stood of old are all too rare. Perhaps they burned down last year, and in their place, another building. Perhaps what was a great house has crumbled away, and now a small house stands there. And those that dwell within the buildings are also thus. The place is the same, and the people here are many, but of the people I knew of old perhaps only one or two remain in twenty or thirty. This morning someone dies, this evening someone is born. Thus are human lives nothing more than bubbles in a stream.

Monday, August 02, 2004

Suicide, Absurdity and The End of The World

Well, at last I have got round to reconstructing my entire blog on blogspot, and from now on, although I shall also be using my Opera blog as a back up, I shall be writing with Blogger, or Blogspot, or whatever it calls itself, as my main blog. So let it be known!

Let me start by talking about two books I have started reading recently. One of them is The Myth of Sisyphus by Albert Camus, and one is The End of Nature by Bill McKibben. The first is a philosophical treatise on suicide and the absurd, and purports to deal with the fundamental question of whether life is worth living. The second is a book about global warming. Both of these books are related to what I hope will be my next novel, namely, Domesday Afternoon, which is currently still in tentative note form.

In order to explain exactly how they are related to this project, it would perhaps be easiest for me to describe a phone conversation that I had with a friend yesterday. I won’t go into details, but he told me that he felt his recent lack of energy was due to his neglecting a pet project of his. “Do you think, then, it’s important to hold on to our dreams?” I asked. His reply was in the affirmative. This is, in fact, something I have myself been pondering lately.

This is probably not an exact quote, but William Burroughs wrote something like the following: “You need your dreams. They are a biologic necessity and your lifeline into space.” He went on to criticise certain scientists who have suggested that it is healthier to forget ones dreams (Burroughs very much identifies our literal, nocturnal dreams with our dreams in the broader sense). “Sure, sure, forget your dreams,” mocks Burroughs, “And make arrangements with a competent mortician.”

I began to explain to my friend how I have always felt the same, that it is important to hold onto one’s dreams, but that recently I have been having trouble reconciling this belief with the ecological Armageddon that the human race now faces. After all, what difference does it make if I write a novel, however good it might be, when the person reading it is swept away by a tidal wave the next moment. It is a particularly difficult dilemma because it seems to me that the destruction of the Earth now taking place is a by-product of personal ambition, of simply wanting things for oneself, and to hell with the future. The desires of the ego lead us to pursue success, material comfort, acclaim and so on, which in turn leads to a civilisation that uses up so much of the Earth’s resources that it is impossible to maintain over any great length of time. So where do my petty little dreams fit into all of this?

Well, I don’t have an easy answer for that, but I do feel that if I simply gave up on writing, gave up on my dreams, that wouldn’t do much good either. Somehow I have to incorporate and awareness of our ecological – and by extension, spiritual – crisis into the writing I am doing, which is my true life’s work. I have to find a way of confronting that crisis in the only thing that I am good at. So the novel Domesday Afternoon deals with a worst case scenario of ecological disaster, and the things in the human psyche that brought it about. But, if such a disaster, in the end, cannot be averted, then the work is still useless. Useless unless it somehow also deals with the question that Camus is facing in The Myth of Sisyphus. Is life worth living? In Camus’ case, he was dealing with the question of suicide. In my case, I must deal with the very similar question of whether it is possible to find meaning in life when on the brink of the apocalypse. As I said to my friend, I have to write in such a way that it is actually worth someone’s while to read what I’ve written the moment before they are swept away by a tidal wave. “Is that really what you think before you sit down to write?” he asked, amused. I answered in the affirmative.

Well, at last I have got round to reconstructing my entire blog on blogspot, and from now on, although I shall also be using my Opera blog as a back up, I shall be writing with Blogger, or Blogspot, or whatever it calls itself, as my main blog. So let it be known!

Let me start by talking about two books I have started reading recently. One of them is The Myth of Sisyphus by Albert Camus, and one is The End of Nature by Bill McKibben. The first is a philosophical treatise on suicide and the absurd, and purports to deal with the fundamental question of whether life is worth living. The second is a book about global warming. Both of these books are related to what I hope will be my next novel, namely, Domesday Afternoon, which is currently still in tentative note form.

In order to explain exactly how they are related to this project, it would perhaps be easiest for me to describe a phone conversation that I had with a friend yesterday. I won’t go into details, but he told me that he felt his recent lack of energy was due to his neglecting a pet project of his. “Do you think, then, it’s important to hold on to our dreams?” I asked. His reply was in the affirmative. This is, in fact, something I have myself been pondering lately.

This is probably not an exact quote, but William Burroughs wrote something like the following: “You need your dreams. They are a biologic necessity and your lifeline into space.” He went on to criticise certain scientists who have suggested that it is healthier to forget ones dreams (Burroughs very much identifies our literal, nocturnal dreams with our dreams in the broader sense). “Sure, sure, forget your dreams,” mocks Burroughs, “And make arrangements with a competent mortician.”

I began to explain to my friend how I have always felt the same, that it is important to hold onto one’s dreams, but that recently I have been having trouble reconciling this belief with the ecological Armageddon that the human race now faces. After all, what difference does it make if I write a novel, however good it might be, when the person reading it is swept away by a tidal wave the next moment. It is a particularly difficult dilemma because it seems to me that the destruction of the Earth now taking place is a by-product of personal ambition, of simply wanting things for oneself, and to hell with the future. The desires of the ego lead us to pursue success, material comfort, acclaim and so on, which in turn leads to a civilisation that uses up so much of the Earth’s resources that it is impossible to maintain over any great length of time. So where do my petty little dreams fit into all of this?

Well, I don’t have an easy answer for that, but I do feel that if I simply gave up on writing, gave up on my dreams, that wouldn’t do much good either. Somehow I have to incorporate and awareness of our ecological – and by extension, spiritual – crisis into the writing I am doing, which is my true life’s work. I have to find a way of confronting that crisis in the only thing that I am good at. So the novel Domesday Afternoon deals with a worst case scenario of ecological disaster, and the things in the human psyche that brought it about. But, if such a disaster, in the end, cannot be averted, then the work is still useless. Useless unless it somehow also deals with the question that Camus is facing in The Myth of Sisyphus. Is life worth living? In Camus’ case, he was dealing with the question of suicide. In my case, I must deal with the very similar question of whether it is possible to find meaning in life when on the brink of the apocalypse. As I said to my friend, I have to write in such a way that it is actually worth someone’s while to read what I’ve written the moment before they are swept away by a tidal wave. “Is that really what you think before you sit down to write?” he asked, amused. I answered in the affirmative.

Feelgood Hit of the Summer

First published on Opera, Thur 27th May, 2004.

This might be the last entry I make in this blog for some time. There are various reasons for this. Firstly, the archives at Opera do not appear to be working, and the enquiry I sent to Opera about this some weeks ago has not been answered, so I am in the process of re-constructing this blog elsewhere. Opera only displays twenty entries on a screen at one time, after that they are archived, which, owing to some fault or other, means they are effectively lost. This is the twentieth entry in my blog. So until I have caught up on my new, re-constructed blog, this, as I say, may be the last entry. If you have followed me thus far, please do not abandon me now!!!!!

Another reason is, I had an interview today and I seem to have got the job, much to my shock and amazement. So, that cuts down my time considerably. The treadmill beckons upon which we all must tread, and which leads eventually over the cliff called ‘Death’. I did try to become a freelance writer, and perhaps I shall rally again after this retreat, but, well, it’s not easy. There is no beaten path for the writer. And there’s precious little respect. Imagine the scene, someone goes into a baker:

Customer: I’ll have one of your buns, please.

Baker: Certainly, that’ll be ninety pence.

Customer: Are you joking? Don’t be so tight-fisted? That’s so mercenary! Come on, you can give me a bun, can’t you?

Baker: Well, I’m afraid I have to charge you, or I won’t be able to buy and eat buns myself.

Customer: I can’t believe that a creative person like a baker can have such a materialistic attitude. I try to do you a favour by eating one of your buns, and what happens? Look, if you let me have the bun, and I like it, I might tell other people to come here for their buns, and some of them might even pay you, if they’re rich or something.

And so on.

It sounds ridiculous, but this is the attitude that people seem to take towards writers. And I’m utterly sick of it.

Anyway, I am really writing this entry in order to review an album. That album is Summerisle. It is the latest release from Momus, and it came out last month. I interviewed Momus prior to its release, and now, having listened to the album a few times, I finally come to write the review as I have long intended. Here goes:

Summerisle is a collaboration between Momus and Anne Laplantine that Momus tells us is based conceptually upon the film The Wickerman. Hearing this, we may imagine that the album is either horrific or cinematic or both. In fact, it is neither. To me, it hardly sounds like ‘an album’ at all. I don’t mean that in a derogatory sense, although it was a little unexpected. Albums, I think, like stories, tend to have a feeling, however tenuous, of beginning, middle and end. Summerisle does not have such a feeling. It is far less dramatically conceived, in fact, than most of Momus’ work, in which a sense of theatre and narrative is often quite prominent.

No, what this album conveys is not drama or narrative so much as daydream. What it has taken from The Wickerman is not horror, but idyll. Perhaps, for me at least, the key to the album is in the word ‘isle’. This music, in the nicest possible way, is not going anywhere. It is happy to enjoy the summer quietly on the little island it has created. Time seems to have stopped on this island. In fact, some of Anne Laplantine’s ambient instrumental doodlings sound to me somehow like a clock might sound trying to tick and to chime in a world without time where its hands, like the needle of a compass in a world with no poles, swing about lost and lazy.

Listening to this music I feel the way I did as a child, listening to some grown-up idly making music in the same room as me while I watched sunlight creep across bare floor-boards. And when I suddenly shiver for no reason, I wonder why it is that that world seems to have disappeared – the world where there was more sense of community and less sense of time, where it was not unusual for someone to sit stroking someone’s hair, saying nothing, for an hour or so.

Momus’ lyrics are usually the kind that you might want to sit down and read for their own sake. On Summerisle his approach is quite different. The opening track has a vocal that seems to consist of chanted made-up words, somewhere between a recital of Japanese Noh drama and someone mumbling to themselves in a dream. Even when the lyrics are at their most coherent and linear, as with a little tale of a tailor who follows a shape-changing hare to a coven of hares, I have the feeling that they are not so much trying to tell a story or make a point, as to conjure up a world in which people had the time to sit around telling such stories to each other.

This is not a dramatic or spectacular album, but if you feel like just lying down and having someone stroke your hair, musically, for half an hour or so, well, Summerisle is the place for you. I don't know about you, but I could certainly do with some time, or no-time, there this summer.

First published on Opera, Thur 27th May, 2004.

This might be the last entry I make in this blog for some time. There are various reasons for this. Firstly, the archives at Opera do not appear to be working, and the enquiry I sent to Opera about this some weeks ago has not been answered, so I am in the process of re-constructing this blog elsewhere. Opera only displays twenty entries on a screen at one time, after that they are archived, which, owing to some fault or other, means they are effectively lost. This is the twentieth entry in my blog. So until I have caught up on my new, re-constructed blog, this, as I say, may be the last entry. If you have followed me thus far, please do not abandon me now!!!!!

Another reason is, I had an interview today and I seem to have got the job, much to my shock and amazement. So, that cuts down my time considerably. The treadmill beckons upon which we all must tread, and which leads eventually over the cliff called ‘Death’. I did try to become a freelance writer, and perhaps I shall rally again after this retreat, but, well, it’s not easy. There is no beaten path for the writer. And there’s precious little respect. Imagine the scene, someone goes into a baker:

Customer: I’ll have one of your buns, please.

Baker: Certainly, that’ll be ninety pence.

Customer: Are you joking? Don’t be so tight-fisted? That’s so mercenary! Come on, you can give me a bun, can’t you?

Baker: Well, I’m afraid I have to charge you, or I won’t be able to buy and eat buns myself.

Customer: I can’t believe that a creative person like a baker can have such a materialistic attitude. I try to do you a favour by eating one of your buns, and what happens? Look, if you let me have the bun, and I like it, I might tell other people to come here for their buns, and some of them might even pay you, if they’re rich or something.

And so on.

It sounds ridiculous, but this is the attitude that people seem to take towards writers. And I’m utterly sick of it.

Anyway, I am really writing this entry in order to review an album. That album is Summerisle. It is the latest release from Momus, and it came out last month. I interviewed Momus prior to its release, and now, having listened to the album a few times, I finally come to write the review as I have long intended. Here goes:

Summerisle is a collaboration between Momus and Anne Laplantine that Momus tells us is based conceptually upon the film The Wickerman. Hearing this, we may imagine that the album is either horrific or cinematic or both. In fact, it is neither. To me, it hardly sounds like ‘an album’ at all. I don’t mean that in a derogatory sense, although it was a little unexpected. Albums, I think, like stories, tend to have a feeling, however tenuous, of beginning, middle and end. Summerisle does not have such a feeling. It is far less dramatically conceived, in fact, than most of Momus’ work, in which a sense of theatre and narrative is often quite prominent.

No, what this album conveys is not drama or narrative so much as daydream. What it has taken from The Wickerman is not horror, but idyll. Perhaps, for me at least, the key to the album is in the word ‘isle’. This music, in the nicest possible way, is not going anywhere. It is happy to enjoy the summer quietly on the little island it has created. Time seems to have stopped on this island. In fact, some of Anne Laplantine’s ambient instrumental doodlings sound to me somehow like a clock might sound trying to tick and to chime in a world without time where its hands, like the needle of a compass in a world with no poles, swing about lost and lazy.

Listening to this music I feel the way I did as a child, listening to some grown-up idly making music in the same room as me while I watched sunlight creep across bare floor-boards. And when I suddenly shiver for no reason, I wonder why it is that that world seems to have disappeared – the world where there was more sense of community and less sense of time, where it was not unusual for someone to sit stroking someone’s hair, saying nothing, for an hour or so.

Momus’ lyrics are usually the kind that you might want to sit down and read for their own sake. On Summerisle his approach is quite different. The opening track has a vocal that seems to consist of chanted made-up words, somewhere between a recital of Japanese Noh drama and someone mumbling to themselves in a dream. Even when the lyrics are at their most coherent and linear, as with a little tale of a tailor who follows a shape-changing hare to a coven of hares, I have the feeling that they are not so much trying to tell a story or make a point, as to conjure up a world in which people had the time to sit around telling such stories to each other.

This is not a dramatic or spectacular album, but if you feel like just lying down and having someone stroke your hair, musically, for half an hour or so, well, Summerisle is the place for you. I don't know about you, but I could certainly do with some time, or no-time, there this summer.

A Cock and Bell Story

First published on Opera, Wed 19th May, 2004.

Recently I have become very world-weary. Who am I kidding? I was born world-weary. But, let’s not get pedantic. I am resigned. I look at the world, and to borrow the American idiom, as we all must, by law, these days, I think to myself, “Yeah, yeah, whatever.” Such is my weariness that I have adopted a certain Morrissey quote as my signature on the Terror Tales message boards. The quote runs thus: “You must be such a fool to pass me by.” Do I feel arrogant adopting such a signature? Do I feel as if I might be a tad paranoid, defensive, self-important? Well, yes, but it can’t be helped. A quote from Philip Larkin comes to mind, “I’m not really that good, it’s just that everyone else is so bad they make me look good.”

But all this is something of a digression. I only wanted to say that, whereas I have reservations about blowing my own trumpet – ahem – I don’t mind blowing someone else’s. Less back strain, for one thing. But seriously, I am about to tell you the story of The Greatest Band That Never Was, namely The Dead Bell, of whom you almost certainly have not heard, and of whom I was a member for some five years or so. I played bass and wrote lyrics for the band. Actually, it was more of a song-writing partnership than a band, consisting of myself and Pete Black, until quite late on when John came along, and at last we did some live stuff. The Dead Bell is not I, and so I do not feel arrogant saying that it – or should I say ‘she’? – was living proof that talent and originality count for nothing in the success stakes, and that being a loud-mouthed pushy git counts for everything.

I will tell the story briefly now, and at greater length later. Pete married my sister, and as a result, as he remarked later in a radio interview, he was contractually obliged to play music with me. We had similar interests and tastes. I played bass guitar and he played spectacularly original lead guitar. We were both bored with the utter lack of imagination in the music scene around us – it’s even worse now, which I would never have believed possible. We jammed. It was just messing around. At first I did bass and vocals, and the band had no name. We made a tape that Pete dubbed ‘marauder music’. It was very messy and raw. I do believe that the first song that could really be called The Dead Bell, though the name was to come later, was one entitle Sleeping on Waves. It consisted of bass, acoustic guitar and lead guitar. I remember that Pete had been listening to U2 and remarked that Bono had obviously just recently learned to play the guitar, because all the songs on the new album were two or three chord tricks. I was about sixteen then, and I had been learning the six-string for some weeks, and I came up with a few chords and some lyrics – heart-rending plea to the person who was at the time the ‘love of my life’ – and Pete came up with a real goose-bumps kind of melody and mesmerising lead guitar loop. In fact, we just kept on playing that loop until one of Pete’s guitar strings broke, and so we finished the recording there.

Later we were to become more purposeful about what we did. We trawled through books of poetry for a band name, and finally settled on The Dead Bell, from a poem by Sylvia Plath, for its abstract quality. For about five years we recorded songs on a four track. Pete’s ability to get good recordings within these technical limitations was was impressive. I still think that the recordings we made piss all over every other recording I’ve heard made on a four track in terms of pure production. Sample the tracks now up at The Dead Bell Archive if you don’t believe me. All recorded on an old four-track, held together with selotape and bits of cardboard.

As The Dead Bell we must have recorded somewhere in the region of forty songs, and during all those years I dreamed of us changing the face of music and even the world. I was a bit of a dreamer, you see. But it was not to be. Perhaps the greatest disappointment of my life was the fact that The Dead Bell came to an end in utter obscurity.

However, recently Pete has informed me that he is playing in a new band called The Cock, about which I am very happy. I think that Pete is a truly original and brilliant musician, and I’d hate to see him let his talent go to waste. Anyway, he has asked me to write lyrics for The Cock, and I have gladly agreed. Here are some lyrics I finished recently. I hope you enjoy them, and I look forward to seeing what The Cock can do with them:

The Middle Men

We are the middle men

The nothing-to-do-but-fiddle men

We know what the public wants Because we've told them time and again

And now we'll take our ninety-five per cent, thank you.

And we're not a charity, you know,

We're here to make money

And we're not ashamed, and what's more,

We're here to make sure

That everywhere you go it's just the same

And you can't blame us 'coz

We're only giving people what they want, you know,

And if we didn't do it someone else would have a go

And there are so many shits lining up to replace us

It only goes to show, and oh, it vindicates us

When we advertise the babies

With gene-designer labels

And copyright for Doctor Spin

The medicines we helped push through

To drug the soldiers that we need

To secure the oil fields

For the cars we advertise

To drive the government to modify

Whatever people buy.

We are the middle men

And we'll take our ten per cent

And then another ten, and ten again

And then some more and then some

I'd say we're truly indispensible, wouldn't you?

And it's true we can't create

But what we can do

Is mistranslate your creativity for you

At competitive rates

Our genius lies in making sure

That nothing comes out straight

But we're only giving people what they want etc. etc. etc.

First published on Opera, Wed 19th May, 2004.

Recently I have become very world-weary. Who am I kidding? I was born world-weary. But, let’s not get pedantic. I am resigned. I look at the world, and to borrow the American idiom, as we all must, by law, these days, I think to myself, “Yeah, yeah, whatever.” Such is my weariness that I have adopted a certain Morrissey quote as my signature on the Terror Tales message boards. The quote runs thus: “You must be such a fool to pass me by.” Do I feel arrogant adopting such a signature? Do I feel as if I might be a tad paranoid, defensive, self-important? Well, yes, but it can’t be helped. A quote from Philip Larkin comes to mind, “I’m not really that good, it’s just that everyone else is so bad they make me look good.”

But all this is something of a digression. I only wanted to say that, whereas I have reservations about blowing my own trumpet – ahem – I don’t mind blowing someone else’s. Less back strain, for one thing. But seriously, I am about to tell you the story of The Greatest Band That Never Was, namely The Dead Bell, of whom you almost certainly have not heard, and of whom I was a member for some five years or so. I played bass and wrote lyrics for the band. Actually, it was more of a song-writing partnership than a band, consisting of myself and Pete Black, until quite late on when John came along, and at last we did some live stuff. The Dead Bell is not I, and so I do not feel arrogant saying that it – or should I say ‘she’? – was living proof that talent and originality count for nothing in the success stakes, and that being a loud-mouthed pushy git counts for everything.

I will tell the story briefly now, and at greater length later. Pete married my sister, and as a result, as he remarked later in a radio interview, he was contractually obliged to play music with me. We had similar interests and tastes. I played bass guitar and he played spectacularly original lead guitar. We were both bored with the utter lack of imagination in the music scene around us – it’s even worse now, which I would never have believed possible. We jammed. It was just messing around. At first I did bass and vocals, and the band had no name. We made a tape that Pete dubbed ‘marauder music’. It was very messy and raw. I do believe that the first song that could really be called The Dead Bell, though the name was to come later, was one entitle Sleeping on Waves. It consisted of bass, acoustic guitar and lead guitar. I remember that Pete had been listening to U2 and remarked that Bono had obviously just recently learned to play the guitar, because all the songs on the new album were two or three chord tricks. I was about sixteen then, and I had been learning the six-string for some weeks, and I came up with a few chords and some lyrics – heart-rending plea to the person who was at the time the ‘love of my life’ – and Pete came up with a real goose-bumps kind of melody and mesmerising lead guitar loop. In fact, we just kept on playing that loop until one of Pete’s guitar strings broke, and so we finished the recording there.

Later we were to become more purposeful about what we did. We trawled through books of poetry for a band name, and finally settled on The Dead Bell, from a poem by Sylvia Plath, for its abstract quality. For about five years we recorded songs on a four track. Pete’s ability to get good recordings within these technical limitations was was impressive. I still think that the recordings we made piss all over every other recording I’ve heard made on a four track in terms of pure production. Sample the tracks now up at The Dead Bell Archive if you don’t believe me. All recorded on an old four-track, held together with selotape and bits of cardboard.

As The Dead Bell we must have recorded somewhere in the region of forty songs, and during all those years I dreamed of us changing the face of music and even the world. I was a bit of a dreamer, you see. But it was not to be. Perhaps the greatest disappointment of my life was the fact that The Dead Bell came to an end in utter obscurity.

However, recently Pete has informed me that he is playing in a new band called The Cock, about which I am very happy. I think that Pete is a truly original and brilliant musician, and I’d hate to see him let his talent go to waste. Anyway, he has asked me to write lyrics for The Cock, and I have gladly agreed. Here are some lyrics I finished recently. I hope you enjoy them, and I look forward to seeing what The Cock can do with them:

The Middle Men

We are the middle men

The nothing-to-do-but-fiddle men

We know what the public wants Because we've told them time and again

And now we'll take our ninety-five per cent, thank you.

And we're not a charity, you know,

We're here to make money

And we're not ashamed, and what's more,

We're here to make sure

That everywhere you go it's just the same

And you can't blame us 'coz

We're only giving people what they want, you know,

And if we didn't do it someone else would have a go

And there are so many shits lining up to replace us

It only goes to show, and oh, it vindicates us

When we advertise the babies

With gene-designer labels

And copyright for Doctor Spin

The medicines we helped push through

To drug the soldiers that we need

To secure the oil fields

For the cars we advertise

To drive the government to modify

Whatever people buy.

We are the middle men

And we'll take our ten per cent

And then another ten, and ten again

And then some more and then some

I'd say we're truly indispensible, wouldn't you?

And it's true we can't create

But what we can do

Is mistranslate your creativity for you

At competitive rates

Our genius lies in making sure

That nothing comes out straight

But we're only giving people what they want etc. etc. etc.