Links

- STOP ESSO

- The One and Only Bumbishop

- Hertzan Chimera's Blog

- Strange Attractor

- Wishful Thinking

- The Momus Website

- Horror Quarterly

- Fractal Domains

- .alfie.'s Blog

- Maria's Fractal Gallery

- Roy Orbison in Cling Film

- Iraq Body Count

- Undo Global Warming

- Bettie Page - We're Not Worthy!

- For the Discerning Gentleman

- All You Ever Wanted to Know About Cephalopods

- The Greatest Band that Never Were - The Dead Bell

- The Heart of Things

- Weed, Wine and Caffeine

- Division Day

- Signs of the Times

Archives

- 05/01/2004 - 06/01/2004

- 06/01/2004 - 07/01/2004

- 07/01/2004 - 08/01/2004

- 08/01/2004 - 09/01/2004

- 09/01/2004 - 10/01/2004

- 10/01/2004 - 11/01/2004

- 11/01/2004 - 12/01/2004

- 12/01/2004 - 01/01/2005

- 01/01/2005 - 02/01/2005

- 02/01/2005 - 03/01/2005

- 03/01/2005 - 04/01/2005

- 05/01/2005 - 06/01/2005

- 06/01/2005 - 07/01/2005

- 07/01/2005 - 08/01/2005

- 08/01/2005 - 09/01/2005

- 09/01/2005 - 10/01/2005

- 10/01/2005 - 11/01/2005

- 11/01/2005 - 12/01/2005

- 12/01/2005 - 01/01/2006

- 01/01/2006 - 02/01/2006

- 02/01/2006 - 03/01/2006

- 09/01/2006 - 10/01/2006

- 10/01/2006 - 11/01/2006

- 11/01/2006 - 12/01/2006

- 12/01/2006 - 01/01/2007

- 01/01/2007 - 02/01/2007

- 02/01/2007 - 03/01/2007

- 03/01/2007 - 04/01/2007

- 04/01/2007 - 05/01/2007

- 05/01/2007 - 06/01/2007

- 06/01/2007 - 07/01/2007

- 07/01/2007 - 08/01/2007

- 08/01/2007 - 09/01/2007

- 09/01/2007 - 10/01/2007

- 10/01/2007 - 11/01/2007

- 11/01/2007 - 12/01/2007

- 12/01/2007 - 01/01/2008

- 01/01/2008 - 02/01/2008

- 02/01/2008 - 03/01/2008

- 03/01/2008 - 04/01/2008

- 04/01/2008 - 05/01/2008

- 07/01/2008 - 08/01/2008

Being an Archive of the Obscure Neural Firings Burning Down the Jelly-Pink Cobwebbed Library of Doom that is The Mind of Quentin S. Crisp

Tuesday, July 29, 2008

The Trees are the View

Since Friday I have been in Devon, where I was born and grew up. I have come here directly from Wales and notice some differences. My current Welsh location is very much 'the countryside', as is the area in Devon where I grew up. But Devon, it seems to me, is a lighter place, where it is easier to breathe, perhaps because the shadow of industry has never fallen across its soul.

There are certain delights to be had in revisiting one's old home that I do not intend to describe at length. Anyone who has read my short story 'Decay' might have some idea of them. Perhaps I can sum those delights up as the perfume of mildewed books. Since coming here I have, quite naturally, looked to my old sagging bookshelves, to remember what has been gathering dust, and I have pulled a few volumes off the shelves to take back with me to Wales, and I have inhaled the musty spores of exquisite decay that rise from their pages.

One of the volumes that I have been looking at is William Burroughs's The Western Lands. I have long wished to unearth a favourite passage from this book, which I have not found excerpted on the Internet. After trawling through the book for some time, I have discovered that the favourite passage is, in fact, not one passage, but a number of scattered passages on a related theme. I have put together such of those scattered parts as I found at the top of this entry, to recreate the passage as I remembered it, or almost, in my own little cut-up. The parts that are missing deal with Burroughs's idea of a Creator who existed before the Christian god, and whose Creation the Christian god stole. They also deal with the idea of mass-production setting in not only in human society, but as a kind of evolutionary spirit or trend, blocking the further creation of such beautiful, delicate one-offs as the aye-aye. Responsible for this ugly mass-production are both Christianity and science.

Since coming back to Devon this time, I have also had cause to ponder another passage from the work of William Burroughs, this time from (I believe) My Education: A Book of Dreams. In it he bemoans the destruction of the natural environment by human beings, mentioning the argument often given that the human beings in question - poachers, for instance - are just trying to survive. He dismisses this argument, saying something like, "So what? I don't care about these people. There are too many humans, anyway." I admire the forthright expression of his feelings here. Usually only children are uncorrupted enough to say such things. I know that I felt exactly the same way as a child, and reading this I had to wonder why in adult life I tend to soften my views. Why do I wish to make myself agreeable to people when I know very well that people are stupid and disgusting?

Soon after my arrival here, discussion that took place was naturally about what has changed and what remains the same since my last visit. The house is located down a dead-end little dirt track opposite hills and fields. Apparently, someone down this road started a petition in order to gain permission from the local council to cut down the trees along the hedge on the other side of the track, because they were 'blocking the view'. It seems enough residents of this road signed the petition for their will to prevail, and I don't suppose any local council anywhere has ever been averse to chopping down trees, anyway, since the prime delight of all who serve on such councils seems to be to vandalise all that is beautiful in the world and replace it with all that is petty and mundane. Trees spoiling the view? What sort of education, in what sort of culture, have these people had? The trees are the view. Naturally, I heaved a sigh, and quietly wished unpleasant death to visit all those who had signed the petition, as soon as possible. And, perhaps not as naturally, but with myself, at least, quite expectedly, I also felt guilty for wishing such a thing.

Later, walking by myself on the hill near the house, which overlooks the sea, I realised again that the closest I come to well-being is when I am among trees. I feel that I am myself again, and nothing of that other world - the human world - matters. It came to me also, as I walked the hill in the green and grey cool of dove-boughed avenues, that it is only proper that I should despise the mass of humanity; the mass of humanity is despicable. There is nothing wrong with my anger, and if I felt as naturally myself at all times as I do when walking among the trees I have known since childhood, then I would be quite calm about my anger, and there would be no malice in it. Even if I wished death upon some idiot - (isn't that line from the Bowie song, "I could spit in the eyes of fools", actually, absolutely right? - it would be wished without malice. It would be of the moment, and the next moment, purified, I would forget it.

I hear also that developers have plans - so far thwarted - for the currently wild slope from the edge of this dirt track to the valley below. I hereby wish unpleasant death to come speedily upon any would-be developers, and call upon the gods of the Owl cults, with their wrenching needle talons, to shred the developers's hearts, that they might die shrieking like little girls while blood pours in gouts from mouth, ears and eyes.

I write that quite without malice, of course.

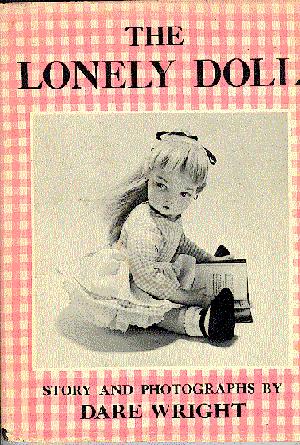

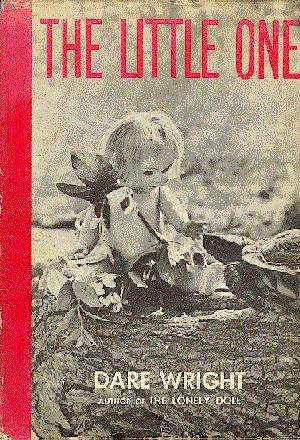

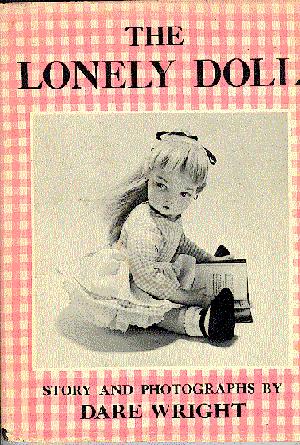

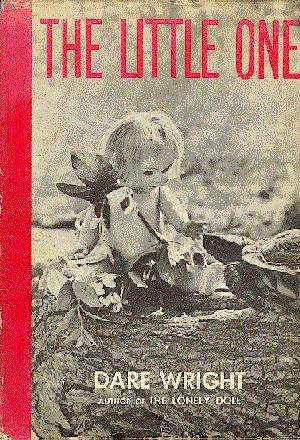

This brings me to Dare Wright, who has a place of honour in my temple - an altar of her own. It was quite natural that, coming back to Devon this time, and ferreting among my old books, I should in particular wish to find the works of Dare Wright, which were known to me as a child, but which in adult life have only ever been a memory. They were easily found. There were two of them (there may have been another, which has disappeared), The Lonely Doll and The Little One. The former appears to be a second edition, and the latter a first. They are musty in a way that complements the pictures and the stories wonderfully. I have not read these books since childhood, so it was quite possible that, adult in years now, I would be disappointed by what I read. But I was not.

It seems to me that Dare Wright is a true original, and has done what originals do. Not only has she expressed something original, but her means of expression has been original, too, and it is perhaps this latter half of creative originality that so often baffles people, though the two halves are hard to separate. In any case, I feel that Dare Wright is someone who created with love, and it is no wonder, therefore, that so many in the world - dull-witted newspaper columnists and others who may as well sit on the local council and plan which trees they are next to murder - think that her work was kitsch, or that she was a crank, or, as Houellebecq wrote of "moralists" in connection to Lovecraft's hatred of adult life, "utter vague opprobrious grumblings while waiting for a chance to strike with their obscene intimations". The obscene intimations of the dull and dull-witted defenders of adulthood in this case are, predictably, to do with Dare Wright's sex life, or her lack of one, over which they hold a prurient clinic in the arrogant manner of psychiatrists, sure that they have more insight into Dare Wright's 'problems' than she had.

To pass one's life in the twentieth century (perhaps in any age), without submitting to the obligatory sexual relations of social belonging that are, in fact, as dull as commerce in the adult sensibleness of the assumptions they represent, seems to me a wonderful acheivement, and is one that I straightforwardly admire, however many psychologists, amateur or otherwise, buzz around the matter like poisonous flies, "waiting for a chance to strike with their obscene intimations".

M.G. Lord, reviewing a biography of Wright for The New York Times, claims to find the biographer more interesting than her subject. His/her insinuations begin in the opening paragraph:

Oozing through the text we find the vile but all-too-common distrust of those who have not bred, of those who have not added to the population of this dull and commerce-led world. It doesn't take long for the insinuations to become outright slurs on Wright's character:

Frigid? Isn't that the word that self-satisfied cads use to describe women who won't sleep with them, or other women use in battles of sexual competitiveness? M.G. Lord goes on to describe Wright's art as "accidental and campy", and compares her unfavourably with Henry James, who, of course, represents all things adult and realistic. "Grow up!" s/he seems to be saying to Wright. "Grow up and get a man and have children of your own!" And cut down more trees in the grove of childhood and bring the developers in to build your new home. Such is M.G. Lord, such are the "moralists".

When I read such reviews, written about those few human beings who have managed to touch me, by one of the dull majority who disgust me, I tend to think of the lines from Reel Around the Fountain, by The Smiths:

What has M.G. Lord given me? S/he has offered a slice of deadening criticism. What has Dare Wright given me? Oh, I can tell you, she is so much more alive than M.G. Lord that you would not believe. It also seems significant to me that the first lines in Reel Around the Fountain are, "It's time the tale were told/Of how you took a child/And you made him old". This is simply what the amassed ranks of sensible society, arms crossed, lips pursed, shaking their heads, do to children - they make us old. They cut down more trees in our grove. But when we recognise another child-spirit like our own, we find some way to escape from those gathered ranks of sensible adult humans. We find the cool of the sacred grove, where no one else goes, and there, well, there we find a fountain to reel around.

To me, though I never met her, Dare Wright is undoubtedly one of the beautiful people. In her book The Little One, she tells the story - and shows it, too, with her own wonderful photographs - of a doll called Persis, who for some time has been gathering dust on a bookshelf in an abandoned house. A turtle comes to the house one day, finds her, and liberates her. Hot in the wild summer grasses, she comes upon a butterfly, who advises her she would be more comfortable without her clothes. Liberated, once again, as she divests herself of her clothes, she falls asleep beneath a "baby tree". There she is found by two bears, one of whom is happy and one of whom is grumpy. They wake her, and immediately she springs up with arms outstretched and says, "I like you". She lives then, with the bears, in the woods, where she wears skirts of leaves and ferns, there in the sacred monochrome cool of damp earth and sylvan shade. She rides upon Turtle's back, with a saddle of moss, like Lady Godiva, and bathes at the edges of waterfalls. This is what is done in the sacred grove. Eventually, she climbs a great tree in search of honey to appease the Cross Bear, who she thinks does not love her. When she falls from that tree, Cross Bear takes her in his arms, and she discovers that he does love her.

It is hard to describe exactly what this story means to me, because so much of it relies on the photographs, which are far too wonderful, eerie, expansive and mysterious to be "accidental" as M.G. Lord seems to think them. But I know when I read this that Wright was someone who was ready to meet you there - in her books at least - away from the dull developers of the adult world, in that shady grove. And that, not the adult commerce of sex, is love. And now I am reminded of that strange and wonderful contrast between the songs Pretty Girls Make Graves and The Hand that Rocks the Cradle on the first Smiths album. The first song shows the despair that attends the workings of lust and competitive sexuality in human society ("I lost my faith in womanhood"), and the second, which follows immediately, shows something purer and deeper - the love of, or for, a child: "Please don't cry/For the ghost and the storm outside/Will not invade this sacred shrine/Or infiltrate your mind/My life down I shall lie/If the bogeyman should try/To play tricks on your sacred mind/To tease, torment or tantalise."

Also from The New York Times, this time by one David Colman, we have another article on Dare Wright. M.G. Lord was amongst the camp that try to dismiss with an authoritative sniff, using words such as "campy". David Colman still ranks in that dull majority, but his word of choice is "unsettling". This is only slightly preferable. He seems to invite Wright in for a while, but ultimately there is rejection here. He wants to appear to be considering opening the door before he slams it. This is how the article begins:

So, why did the eternally hip Kim Gordon think better of it? She found it "too depressing", and she was concerned about the spanking scene. It might be "sadistic". Kim Gordon, who describes the work as both "creepy" and "compelling", ultimately wants to keep it away from her child. A similar attitude is expressed by Elizabeth Karlsen, who may be producing the film of Wright's life. It is interesting that so many people fascinated by Wright should treat her more like a case study than a human being, perhaps in the way that well-to-do Victorians would pay for a nice day out at the lunatic asylum before retiring to their respectable homes. Karlsen wonders if The Lonely Doll really fits in with the standards of today's world. Yes, "today's standards". That's what she's worried about. The same standards by which Kim Gordon also judges the book. How very hip. I mean, that really is very hip, isn't it - worrying about today's standards. That's what being hip means. I wrote recently that it's a good thing to realise that literature is better than rock'n'roll, and this is what I was talking about. Rock'n'roll (I don't know if Sonic Youth is generally thought of as such, but that's what it is, basically, a form of music made by young people that is designed to be rebellious) is, in the end, a form of social climbing. There are dreams of literature, and there are dreams of rock'n'roll, and there's certainly some crossover, but the dreams of the latter are more likely to be those kind synonymous with ambition and worldly success. Rock'n'roll has a greater reputation for rebellion than do the sometimes, er... bookish types who tend to represent literature. But it seems to me that you are more likely to find a true outsider in literature than in rock'n'roll, and the story of Kim Gordon and Dare Wright is a case in point. Kim Gordon is unsettled by Dare Wright - by Dare Wright, the cosy old writer of children's stories. Kim Gordon is hip and is therefore susceptible to hip - and essentially bourgeious - social influences like political correctness. What outsider ever cared about political correctness? Tell me. The answer is that none ever have.

Rock'n'roll rebels are unlikely to be true outsiders. The chances are that in their hearts they are middle-class social climbers. They are interested in social reform and other such cosmetic things. They discover the symbols left to the world by true outsiders - the ones that rarely got the fame and the money - and they wear them as fashion statements. But they take those outfits off again later, when they are relaxing at home, with their own children. They are outsiders only in externals. They have simply discovered outsiderness. And this is why their music gets worse and worse as they get older. They don't have their own direct contact with the sacred grove of the outsider that is the source of imagination and creativity. Rock'n'roll, in the orthodoxy of its rebellion, is unable to address death, unless it is the death of the young, when rock'n'roll comes into its own. Otherwise, it simply becomes more and more ridiculous as its purveyors age, while the creators of literature, familiar with death from the shadows in the grove of the outsider, come more and more into their own with age. Rock'n'rollers never really wanted to be outsiders - they wanted to succeed... by appearing to be outsiders. The true outsiders might or might not succeed, but they will always be outsiders. M.G. Lord may be right about Dare Wright's art being "accidental" in one sense - the outsider cannot help being the outsider. And in that sense, all great art is accidental. It's not the business-plan of the developers and the rock'n'rollers.

On Saturday, I watched the film Miss Potter, about another writer of children's stories, the famous Beatrix Potter. I'm not going to critique the film beyond saying I thought it was made simple for wide public consumption. (By co-incidence I notice that it has just been Beatrix Potter's birthday.) Beatrix Potter also seemed to dwell, as outsiders do, in her private imagination. And for her, as for myself, that imagination was linked to nature. She had her sacred grove in the Lake District. Happily, she was one outsider who also knew success. With the money she made from her books - which was considerable - she bought up thousands of acres of land in the Lake District to save it from the developers for the benefit of future generations. I wonder how many rich rock'n'rollers have the imagination even to do that much with their money.

I have probably written too much. The world saddens me. There are one or two beautiful ones that I can meet in that shady grove. As to the rest, I curse humanity. I curse a humanity that doesn't notice or care when the writer Thomas Disch, threatened with eviction in his old age, resorts to suicide. I curse a world that favours Jane Austen over Arthur Machen. I curse a society in which people think that trees block the view. I curse you, and I do the only thing that I can do, and retreat to that grove, while it still stands.

The Hawk cults, blue eyes harsh and pitiless as the sun; the Owl cults, with huge yellow night eyes and wrenching needle talons; flying weasels and reptiles...

But the One God has time and weight. Heavy as the pyramids, immeasurably impacted, the One God can wait. The Many Gods may have no more time than the butterfly, fragile and sad as a boat of dead leaves, or the transparent bats who emerge once every seven years to fill the air with impossible riots of perfume.

At the sight of the Black Lemur, with round eyes and a little red tongue protruding, the writer experiences a delight that is almost painful... the silky hair, the shiny black nose, the blazing innocence. Bush Babies with huge round yellow eyes, fingers and toes equipped with little sucker pads... a Wolverine with thick, black fur, body flat on the ground, head tilted up to show its teeth in a smirk of vicious depravity. (He marks his food with a musk that no other animal can tolerate.) The beautiful Ring-Tailed Lemur, that hops along through the forest as if riding a pogo stick, the Gliding Lemur with two curious folds in his brain. The Aye-aye, one of the rarest of animals, cat-size, with a long, bushy tail, round orange eyes and thin bony fingers, each tipped with a long needle claw. So many creatures, and he loves them all.

So who made all the beautiful creatures, the cats and lemurs and minks, the tiny delicate antelopes, the deadly blue krait, the trees and lakes, the seas and mountains? Those who can create. No scientist could think it up. They have turned their backs on creation.

Since Friday I have been in Devon, where I was born and grew up. I have come here directly from Wales and notice some differences. My current Welsh location is very much 'the countryside', as is the area in Devon where I grew up. But Devon, it seems to me, is a lighter place, where it is easier to breathe, perhaps because the shadow of industry has never fallen across its soul.

There are certain delights to be had in revisiting one's old home that I do not intend to describe at length. Anyone who has read my short story 'Decay' might have some idea of them. Perhaps I can sum those delights up as the perfume of mildewed books. Since coming here I have, quite naturally, looked to my old sagging bookshelves, to remember what has been gathering dust, and I have pulled a few volumes off the shelves to take back with me to Wales, and I have inhaled the musty spores of exquisite decay that rise from their pages.

One of the volumes that I have been looking at is William Burroughs's The Western Lands. I have long wished to unearth a favourite passage from this book, which I have not found excerpted on the Internet. After trawling through the book for some time, I have discovered that the favourite passage is, in fact, not one passage, but a number of scattered passages on a related theme. I have put together such of those scattered parts as I found at the top of this entry, to recreate the passage as I remembered it, or almost, in my own little cut-up. The parts that are missing deal with Burroughs's idea of a Creator who existed before the Christian god, and whose Creation the Christian god stole. They also deal with the idea of mass-production setting in not only in human society, but as a kind of evolutionary spirit or trend, blocking the further creation of such beautiful, delicate one-offs as the aye-aye. Responsible for this ugly mass-production are both Christianity and science.

Since coming back to Devon this time, I have also had cause to ponder another passage from the work of William Burroughs, this time from (I believe) My Education: A Book of Dreams. In it he bemoans the destruction of the natural environment by human beings, mentioning the argument often given that the human beings in question - poachers, for instance - are just trying to survive. He dismisses this argument, saying something like, "So what? I don't care about these people. There are too many humans, anyway." I admire the forthright expression of his feelings here. Usually only children are uncorrupted enough to say such things. I know that I felt exactly the same way as a child, and reading this I had to wonder why in adult life I tend to soften my views. Why do I wish to make myself agreeable to people when I know very well that people are stupid and disgusting?

Soon after my arrival here, discussion that took place was naturally about what has changed and what remains the same since my last visit. The house is located down a dead-end little dirt track opposite hills and fields. Apparently, someone down this road started a petition in order to gain permission from the local council to cut down the trees along the hedge on the other side of the track, because they were 'blocking the view'. It seems enough residents of this road signed the petition for their will to prevail, and I don't suppose any local council anywhere has ever been averse to chopping down trees, anyway, since the prime delight of all who serve on such councils seems to be to vandalise all that is beautiful in the world and replace it with all that is petty and mundane. Trees spoiling the view? What sort of education, in what sort of culture, have these people had? The trees are the view. Naturally, I heaved a sigh, and quietly wished unpleasant death to visit all those who had signed the petition, as soon as possible. And, perhaps not as naturally, but with myself, at least, quite expectedly, I also felt guilty for wishing such a thing.

Later, walking by myself on the hill near the house, which overlooks the sea, I realised again that the closest I come to well-being is when I am among trees. I feel that I am myself again, and nothing of that other world - the human world - matters. It came to me also, as I walked the hill in the green and grey cool of dove-boughed avenues, that it is only proper that I should despise the mass of humanity; the mass of humanity is despicable. There is nothing wrong with my anger, and if I felt as naturally myself at all times as I do when walking among the trees I have known since childhood, then I would be quite calm about my anger, and there would be no malice in it. Even if I wished death upon some idiot - (isn't that line from the Bowie song, "I could spit in the eyes of fools", actually, absolutely right? - it would be wished without malice. It would be of the moment, and the next moment, purified, I would forget it.

I hear also that developers have plans - so far thwarted - for the currently wild slope from the edge of this dirt track to the valley below. I hereby wish unpleasant death to come speedily upon any would-be developers, and call upon the gods of the Owl cults, with their wrenching needle talons, to shred the developers's hearts, that they might die shrieking like little girls while blood pours in gouts from mouth, ears and eyes.

I write that quite without malice, of course.

This brings me to Dare Wright, who has a place of honour in my temple - an altar of her own. It was quite natural that, coming back to Devon this time, and ferreting among my old books, I should in particular wish to find the works of Dare Wright, which were known to me as a child, but which in adult life have only ever been a memory. They were easily found. There were two of them (there may have been another, which has disappeared), The Lonely Doll and The Little One. The former appears to be a second edition, and the latter a first. They are musty in a way that complements the pictures and the stories wonderfully. I have not read these books since childhood, so it was quite possible that, adult in years now, I would be disappointed by what I read. But I was not.

It seems to me that Dare Wright is a true original, and has done what originals do. Not only has she expressed something original, but her means of expression has been original, too, and it is perhaps this latter half of creative originality that so often baffles people, though the two halves are hard to separate. In any case, I feel that Dare Wright is someone who created with love, and it is no wonder, therefore, that so many in the world - dull-witted newspaper columnists and others who may as well sit on the local council and plan which trees they are next to murder - think that her work was kitsch, or that she was a crank, or, as Houellebecq wrote of "moralists" in connection to Lovecraft's hatred of adult life, "utter vague opprobrious grumblings while waiting for a chance to strike with their obscene intimations". The obscene intimations of the dull and dull-witted defenders of adulthood in this case are, predictably, to do with Dare Wright's sex life, or her lack of one, over which they hold a prurient clinic in the arrogant manner of psychiatrists, sure that they have more insight into Dare Wright's 'problems' than she had.

To pass one's life in the twentieth century (perhaps in any age), without submitting to the obligatory sexual relations of social belonging that are, in fact, as dull as commerce in the adult sensibleness of the assumptions they represent, seems to me a wonderful acheivement, and is one that I straightforwardly admire, however many psychologists, amateur or otherwise, buzz around the matter like poisonous flies, "waiting for a chance to strike with their obscene intimations".

M.G. Lord, reviewing a biography of Wright for The New York Times, claims to find the biographer more interesting than her subject. His/her insinuations begin in the opening paragraph:

MANY distinguished children's writers haven't had children of their own -- or, for that matter, conventional family lives. Lewis Carroll, a lifelong bachelor, enjoyed a famously eyebrow-raising attachment to the little girl who inspired ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland.'' George Selden, the unmarried author of ''The Cricket in Times Square,'' also wrote ''The Story of Harold,'' a pseudonymous, semi-autobiographical adult novel that dealt with bisexuality and sadomasochism.

Oozing through the text we find the vile but all-too-common distrust of those who have not bred, of those who have not added to the population of this dull and commerce-led world. It doesn't take long for the insinuations to become outright slurs on Wright's character:

In real life, however, Wright was a mess: a frigid, miserable woman locked in a suffocating relationship with her monstrous mother, with whom she slept, nestling ''like spoons,'' until the older woman finally died in 1975.

Frigid? Isn't that the word that self-satisfied cads use to describe women who won't sleep with them, or other women use in battles of sexual competitiveness? M.G. Lord goes on to describe Wright's art as "accidental and campy", and compares her unfavourably with Henry James, who, of course, represents all things adult and realistic. "Grow up!" s/he seems to be saying to Wright. "Grow up and get a man and have children of your own!" And cut down more trees in the grove of childhood and bring the developers in to build your new home. Such is M.G. Lord, such are the "moralists".

When I read such reviews, written about those few human beings who have managed to touch me, by one of the dull majority who disgust me, I tend to think of the lines from Reel Around the Fountain, by The Smiths:

Fifteen minutes with you

Well, I wouldn't say no

Oh, people said that you were virtually dead

And they were so wrong

What has M.G. Lord given me? S/he has offered a slice of deadening criticism. What has Dare Wright given me? Oh, I can tell you, she is so much more alive than M.G. Lord that you would not believe. It also seems significant to me that the first lines in Reel Around the Fountain are, "It's time the tale were told/Of how you took a child/And you made him old". This is simply what the amassed ranks of sensible society, arms crossed, lips pursed, shaking their heads, do to children - they make us old. They cut down more trees in our grove. But when we recognise another child-spirit like our own, we find some way to escape from those gathered ranks of sensible adult humans. We find the cool of the sacred grove, where no one else goes, and there, well, there we find a fountain to reel around.

To me, though I never met her, Dare Wright is undoubtedly one of the beautiful people. In her book The Little One, she tells the story - and shows it, too, with her own wonderful photographs - of a doll called Persis, who for some time has been gathering dust on a bookshelf in an abandoned house. A turtle comes to the house one day, finds her, and liberates her. Hot in the wild summer grasses, she comes upon a butterfly, who advises her she would be more comfortable without her clothes. Liberated, once again, as she divests herself of her clothes, she falls asleep beneath a "baby tree". There she is found by two bears, one of whom is happy and one of whom is grumpy. They wake her, and immediately she springs up with arms outstretched and says, "I like you". She lives then, with the bears, in the woods, where she wears skirts of leaves and ferns, there in the sacred monochrome cool of damp earth and sylvan shade. She rides upon Turtle's back, with a saddle of moss, like Lady Godiva, and bathes at the edges of waterfalls. This is what is done in the sacred grove. Eventually, she climbs a great tree in search of honey to appease the Cross Bear, who she thinks does not love her. When she falls from that tree, Cross Bear takes her in his arms, and she discovers that he does love her.

It is hard to describe exactly what this story means to me, because so much of it relies on the photographs, which are far too wonderful, eerie, expansive and mysterious to be "accidental" as M.G. Lord seems to think them. But I know when I read this that Wright was someone who was ready to meet you there - in her books at least - away from the dull developers of the adult world, in that shady grove. And that, not the adult commerce of sex, is love. And now I am reminded of that strange and wonderful contrast between the songs Pretty Girls Make Graves and The Hand that Rocks the Cradle on the first Smiths album. The first song shows the despair that attends the workings of lust and competitive sexuality in human society ("I lost my faith in womanhood"), and the second, which follows immediately, shows something purer and deeper - the love of, or for, a child: "Please don't cry/For the ghost and the storm outside/Will not invade this sacred shrine/Or infiltrate your mind/My life down I shall lie/If the bogeyman should try/To play tricks on your sacred mind/To tease, torment or tantalise."

Also from The New York Times, this time by one David Colman, we have another article on Dare Wright. M.G. Lord was amongst the camp that try to dismiss with an authoritative sniff, using words such as "campy". David Colman still ranks in that dull majority, but his word of choice is "unsettling". This is only slightly preferable. He seems to invite Wright in for a while, but ultimately there is rejection here. He wants to appear to be considering opening the door before he slams it. This is how the article begins:

YOU might think that Kim Gordon, the bass player and singer of the eternally hip downtown band Sonic Youth, would not have much in common with mothers of a more conventional stripe. But a few years ago she had an experience many women her age could relate to. She rediscovered a favorite series of childhood books, ''The Lonely Doll,'' and thought about reading them to her 7-year-old daughter, Coco. Then she thought better of it.

So, why did the eternally hip Kim Gordon think better of it? She found it "too depressing", and she was concerned about the spanking scene. It might be "sadistic". Kim Gordon, who describes the work as both "creepy" and "compelling", ultimately wants to keep it away from her child. A similar attitude is expressed by Elizabeth Karlsen, who may be producing the film of Wright's life. It is interesting that so many people fascinated by Wright should treat her more like a case study than a human being, perhaps in the way that well-to-do Victorians would pay for a nice day out at the lunatic asylum before retiring to their respectable homes. Karlsen wonders if The Lonely Doll really fits in with the standards of today's world. Yes, "today's standards". That's what she's worried about. The same standards by which Kim Gordon also judges the book. How very hip. I mean, that really is very hip, isn't it - worrying about today's standards. That's what being hip means. I wrote recently that it's a good thing to realise that literature is better than rock'n'roll, and this is what I was talking about. Rock'n'roll (I don't know if Sonic Youth is generally thought of as such, but that's what it is, basically, a form of music made by young people that is designed to be rebellious) is, in the end, a form of social climbing. There are dreams of literature, and there are dreams of rock'n'roll, and there's certainly some crossover, but the dreams of the latter are more likely to be those kind synonymous with ambition and worldly success. Rock'n'roll has a greater reputation for rebellion than do the sometimes, er... bookish types who tend to represent literature. But it seems to me that you are more likely to find a true outsider in literature than in rock'n'roll, and the story of Kim Gordon and Dare Wright is a case in point. Kim Gordon is unsettled by Dare Wright - by Dare Wright, the cosy old writer of children's stories. Kim Gordon is hip and is therefore susceptible to hip - and essentially bourgeious - social influences like political correctness. What outsider ever cared about political correctness? Tell me. The answer is that none ever have.

Rock'n'roll rebels are unlikely to be true outsiders. The chances are that in their hearts they are middle-class social climbers. They are interested in social reform and other such cosmetic things. They discover the symbols left to the world by true outsiders - the ones that rarely got the fame and the money - and they wear them as fashion statements. But they take those outfits off again later, when they are relaxing at home, with their own children. They are outsiders only in externals. They have simply discovered outsiderness. And this is why their music gets worse and worse as they get older. They don't have their own direct contact with the sacred grove of the outsider that is the source of imagination and creativity. Rock'n'roll, in the orthodoxy of its rebellion, is unable to address death, unless it is the death of the young, when rock'n'roll comes into its own. Otherwise, it simply becomes more and more ridiculous as its purveyors age, while the creators of literature, familiar with death from the shadows in the grove of the outsider, come more and more into their own with age. Rock'n'rollers never really wanted to be outsiders - they wanted to succeed... by appearing to be outsiders. The true outsiders might or might not succeed, but they will always be outsiders. M.G. Lord may be right about Dare Wright's art being "accidental" in one sense - the outsider cannot help being the outsider. And in that sense, all great art is accidental. It's not the business-plan of the developers and the rock'n'rollers.

On Saturday, I watched the film Miss Potter, about another writer of children's stories, the famous Beatrix Potter. I'm not going to critique the film beyond saying I thought it was made simple for wide public consumption. (By co-incidence I notice that it has just been Beatrix Potter's birthday.) Beatrix Potter also seemed to dwell, as outsiders do, in her private imagination. And for her, as for myself, that imagination was linked to nature. She had her sacred grove in the Lake District. Happily, she was one outsider who also knew success. With the money she made from her books - which was considerable - she bought up thousands of acres of land in the Lake District to save it from the developers for the benefit of future generations. I wonder how many rich rock'n'rollers have the imagination even to do that much with their money.

I have probably written too much. The world saddens me. There are one or two beautiful ones that I can meet in that shady grove. As to the rest, I curse humanity. I curse a humanity that doesn't notice or care when the writer Thomas Disch, threatened with eviction in his old age, resorts to suicide. I curse a world that favours Jane Austen over Arthur Machen. I curse a society in which people think that trees block the view. I curse you, and I do the only thing that I can do, and retreat to that grove, while it still stands.

Labels: Beatrix Potter, Dare Wright, Kim Gordon, Sonic Youth, William Burroughs