Links

- STOP ESSO

- The One and Only Bumbishop

- Hertzan Chimera's Blog

- Strange Attractor

- Wishful Thinking

- The Momus Website

- Horror Quarterly

- Fractal Domains

- .alfie.'s Blog

- Maria's Fractal Gallery

- Roy Orbison in Cling Film

- Iraq Body Count

- Undo Global Warming

- Bettie Page - We're Not Worthy!

- For the Discerning Gentleman

- All You Ever Wanted to Know About Cephalopods

- The Greatest Band that Never Were - The Dead Bell

- The Heart of Things

- Weed, Wine and Caffeine

- Division Day

- Signs of the Times

Archives

- 05/01/2004 - 06/01/2004

- 06/01/2004 - 07/01/2004

- 07/01/2004 - 08/01/2004

- 08/01/2004 - 09/01/2004

- 09/01/2004 - 10/01/2004

- 10/01/2004 - 11/01/2004

- 11/01/2004 - 12/01/2004

- 12/01/2004 - 01/01/2005

- 01/01/2005 - 02/01/2005

- 02/01/2005 - 03/01/2005

- 03/01/2005 - 04/01/2005

- 05/01/2005 - 06/01/2005

- 06/01/2005 - 07/01/2005

- 07/01/2005 - 08/01/2005

- 08/01/2005 - 09/01/2005

- 09/01/2005 - 10/01/2005

- 10/01/2005 - 11/01/2005

- 11/01/2005 - 12/01/2005

- 12/01/2005 - 01/01/2006

- 01/01/2006 - 02/01/2006

- 02/01/2006 - 03/01/2006

- 09/01/2006 - 10/01/2006

- 10/01/2006 - 11/01/2006

- 11/01/2006 - 12/01/2006

- 12/01/2006 - 01/01/2007

- 01/01/2007 - 02/01/2007

- 02/01/2007 - 03/01/2007

- 03/01/2007 - 04/01/2007

- 04/01/2007 - 05/01/2007

- 05/01/2007 - 06/01/2007

- 06/01/2007 - 07/01/2007

- 07/01/2007 - 08/01/2007

- 08/01/2007 - 09/01/2007

- 09/01/2007 - 10/01/2007

- 10/01/2007 - 11/01/2007

- 11/01/2007 - 12/01/2007

- 12/01/2007 - 01/01/2008

- 01/01/2008 - 02/01/2008

- 02/01/2008 - 03/01/2008

- 03/01/2008 - 04/01/2008

- 04/01/2008 - 05/01/2008

- 07/01/2008 - 08/01/2008

Being an Archive of the Obscure Neural Firings Burning Down the Jelly-Pink Cobwebbed Library of Doom that is The Mind of Quentin S. Crisp

Sunday, October 31, 2004

The Sex Life of Worms (Episode Three: The Jangling Rejection of the Seals)

As I contemplated her horizontal trance of twisting – slow, pink, glistening, blind – I was aware of two unusual reactions in myself. First was a comparative lack of the usual relief at escaping the vile burden of pregnancy, that consuming catalyst of replication inside. I had known from the start that my opponent would not put up a sufficient fight to inseminate me, so, for all that our copulation had been rich in many unusual elements, it had been lacking in the suspense of competition. Second was a revival of the cold feeling that had flushed through me when I first noticed this creature. I believe there are fixed word compounds to describe this feeling, but I would prefer to describe it afresh with words of my own. It was a kind of reaching out of my emotions, just as my senses reach out. The pathetic state of my victim somehow moved me as if I were viewing myself. And yet the very fact this was another being, infinitely and eternally removed from my understanding, only made this emotion sharper, more exquisite, and harder to endure. Soon as it had come, though, this feeling burst like a bubble. The attainment of purple was yet a long way off. My self-imposed labour had only just begun.

* * * * *

The next stage of my labour consisted of tracking the thing I had made she to her abode. I withdrew from her slug-bloated, vanquished form, which already seemed to teem with the inner-hatching of odious life, like the multiplying bubbles from the mouth of a dying crustacean. Still bedraggled with her acrid discharges, I hid behind some ornamental stalagmites and waited. At length, as if returning from the swampy realms of some I-dissolving, temporary death, a suggestion of focused awareness informed her flops and twitches and she raised herself to an upright position. I say upright, but there was something bowed about her, as if with the weight of her new burden. She swayed a little, seemingly still dazed. With her senses disordered, she did not seem to be aware of my presence. In an attitude of infinite defeat and infinite resignation, she continued on her way, her wriggle full of the same snags that had first caught my attention and which had made her so painfully appealing.

I gave her a considerable head-start. There was no chance of me mistaking her slime-trail. When eventually I did start on that trail, I thought again of the other, metaphysical trail I followed. At some point it had become a little clearer to me, but I still could not trace it to its final destination. That was only as it should be. Perhaps, though, there was no way ahead at all. I was simply taking those turnings which seemed to have about them the deepest glow of purple.

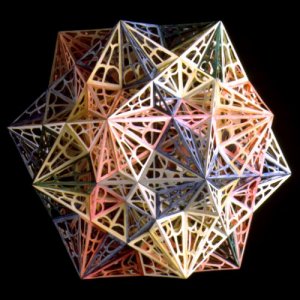

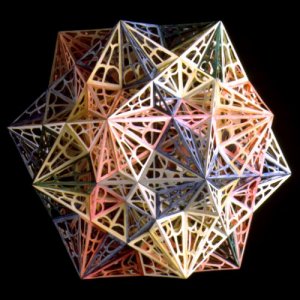

The slime-trail left the old side-burrow and came out on the fringes of a brightly lit commercial district. At first I was disorientated by this sudden shift from soft-hued gloom to dazzling white light. My antennae recoiled and my gills shrivelled. Even when my senses adjusted a little, the activities of the worms to-and-froing in the semi-plaza before me seemed utterly incomprehensible. They descended on the space from long ramps, from bore-holes and wynds, all partaking of the anonymity of elsewhere which was their source. After an interval, rationalisations for their various occupations seeped into my brain; this worm was being re-hydrated, that worm was composing odours at an odour-lamp, this other worm was milking acid glands. Still I reared dumb before this civilised multiplicity, unbounded and undefined by any future as the past is defined by the present. Over all this was impendent a trade and leisure complex of polyhedron cells in three-dimensional tessellation, like a chunk of metal honeycomb that had crashed into the earth. I felt weak and palsied, a mere creature of the caves, suspended amidst nameless things. Does no other feel this way, I wonder, when suddenly confronted with the solid mass of the present?

Taking hold of myself again I remembered my personal mission. I realised that if the she-thing had taken some form of transport from here, particularly if it had been a slime pod, that I might lose the trail. I discovered with some satisfaction, however, that the trail did not even enter the semi-plaza. Instead it smeared off to the left into a ribbed gallery that led eventually to a residential excavation.

The slushy trail was unbroken right to my victim’s apartments. They were of the ambient grotto variety. I reared before an iris-membrane portal in brightly-lit, metal-encased tunnels, surprised that such a malformed creature should inhabit apartments in such a respectable area. Clearly she was a worm of reasonable social status. I could only think that my inference with regard to her exceptional intelligence had been correct. I noted the exact location of these apartments, as well as the date according to sidereal time, and, my business there, for the time being, at an end, I slithered off back to the commercial district I had recently passed.

* * * * *

As I did so I pondered the question of light. When worms are capable of functioning in semi and total darkness, have for the vast bulk of their history, in fact, existed without bright light, what can be the meaning of the modern craze for bathing public spaces in clinical white light? Clearly, any benefits are aesthetic rather than practical. Some worms remind us knowingly that white contains all other colours, implying that it represents the synthesis of all worm thought and experience. I have even heard that some worms have become loath to stray from the light-saturated central areas of Frfrspfshuul. It seems this light gives worms a sense of security, the symbol of our enlightened age. Is this why the memorial of Yqstlss in the Hall of Philosophy is also brightly lit, despite the fact that such lighting would have been unknown to the Grand Philosopharch when shi-he was alive? For myself, I am neither opposed to nor overly fond of the use of white light. I would just like to note that while it makes others feel secure, it makes me feel rootless and alienated.

This feeling bore down on me with some intensity when I arrived back at the semi-plaza and raised my head to take in the great architectural vug of the trade and leisure complex. A rotten hunger had got into me after my exertions. It is at such times of anonymous physicality that I feel most literary. Moments that are lost as soon as they arise. Moments without posterity. Moments of pure waste. Moments such as the allaying of hunger with food, completing a trivial business transaction, feeling the slime of another congeal on one’s skin after sex. I told myself in my weariness that in this sense I was in for a minor literary treat, and reared there proudly for a moment, enjoying the picture of myself in the foreground, the complex the looming background, myself solitary, soiled, with gills dandily plumed and full of the proud swellings of things as yet unwritten.

After slouching faintly up the ramps, automatic and otherwise, that intersected the inside of the complex, I came to a fungus bar that looked suitable. It was an establishment called The Colony. Inside, the general white light of the complex had been dimmed the better to emphasise the polychromatic phosphorescence of the multifarious moulds, fungi and lichens that had been carefully cultivated in the terraced and suspended gardens between the dining areas. The place was seething with customers, more like a newly hatched brood than selected survivors, and their pigmentation squirmed liquidly in social display. The inner walls of this polyhedron were of such blackness that it seemed they were not there at all. Their surfaces were near undetectable, giving only a reflective gleam here and there, and as a result it appeared as if all the gardens and the squillion customers were superimposed garishly upon ultimate nowhere. “Even these nameless squillions are finite,” I thought to myself. An attendant crawled out from the ledger office and approached me. Shi-he was obviously dosed up on the pigmentation inhibitors so common in such service posts, and even wore a dorsal mantle over which played artificial muzak pigmentation. Yet sh-his ventral and anterior colouring, which was still apparent, seemed to me an aggressive mix of red and white.

“I need to check your seals,” shi-he said, extending a braid of slick tentacles.

I retrieved my seal book and my own seal from my pouch and relinquished then to the baffling attendant. Shi-he gave them a cursory inspection, returned sh-his attention to me for a moment of scrutiny whose meaning I could not guess, then crawled back into the ledger office. There, apparently, my seal and book were subjected to closer examination. When the attendant returned I noticed that my seal had not been used. I raised my antennae quizzically.

“No,” said the attendant.

“’No’ is not the answer to my question.”

“No, I cannot permit your partaking of the services and products of this establishment.”

“Is an explanation to be expected?”

I thought I detected a suppressed orange simmering around the attendant’s white mottles.

“There appear to be only two seals in your book.”

“If you inspect it carefully you will be aware that one of those seals belongs to Doctor Jsshloamgs, my mentor.”

“That seal is due to expire.”

“But it has not expired. There is a vital difference there.”

“Your credentials are dubious.”

This remark did not fail to alarm me. I regretted that I too was not under the influence of pigmentation inhibitors. To lose ground in a bluffing match is deadly. I turned away in confusion and let my senses wander flutter-snufflingly over the interior of the bar. They rested finally, flicker-jitteringly, upon a delicate, wispy mould that grew atop a small dais of black crystal. The fibres of the mould were glowing a beautiful moon-dust grey, with the merest suggestion of filmy blue. For a moment this gossamer translucence became a spyglass onto a world of strange longing, where I was lost. Then my senses returned to me. I collected myself.

“One of those seals is fourth and one third level, and judging by the texture of your establishment here, I should not need more. The second seal is from my superior at the seal exchange bureau. I hold a position there. I know something about seals.”

The attendant did not respond. Because of my befuddlement at the exceptional circumstance of being refused service, a suspicion grew on me, turning into fixated conviction, which in retrospect I was to see as a wild misjudgement.

“Do you require money?” I asked.

“Money?” The attendant physically recoiled at this unexpected word.

“There’s no need to be so surprised. It’s common enough to keep some in case of emergencies. If you go to The Crevices they won’t accept anything else. They’re not part of the seal system there.”

It was clear I was only making the situation worse.

“There is no provision made in our accounts for money.”

“Well, then, why not accept my seals? You have no grounds for describing Dr. Jsshloamgs’ seal as ‘dubious’.”

“Business is not as one-dimensional as you think.”

This last insult was delivered in a suppressed hiss. I had been forced into a zone where all dignity was denied me. The vital, naked I flared up from within me, embattled, defending the dignity of its existence beyond dignity.

“Are you questioning my survival skills? You? A purveyor of edible fungi? You who needs pigmentation blockers just to perform your duties? Your type knows nothing of the subtlety of squirming through the sea of bodies that is our race. Uniqueness? Abstraction? It’s quite beyond your sensory range. It would be a satisfactory propriety to take you outside now and inseminate you, but unfortunately I have recently donated. You’d know the tang of my fluids with eggs inside you.”

By this time our altercation had attracted the attention of a number of the guests. I had been unable to keep myself from flashing in a variety of anti-social patterns. I realised it was time for me to cut my losses and leave.

* * * * *

Purple, I say.

The chagrin, the sickness of rearing my conscious head alone. There is a plateau, high and empty. Surrounded only by so far away, so far away, I, uncrowned by the ultimate self that is by right of this existence mine, through tunnels that enclose me in all directions, doppelganger me with strange and isolating limitations, am battered and turned aside. Sashaying, sashaying, squirming, wriggle-looping, blind as the curving tunnels, blind as movement only, sticking with the threads of my skin-slime to the bedrock that remains the same as I forever peel myself away.

Tunnels wander into an abandoned, draughty zone were time is as circuitous as they. Veering up and wide towards the surface to a nowhere hump that I know wordlessly, where the outer light creeps through a crack. Exhausted, I rest. The light that is external to everything I know coats my gills like spittle. I am half absorbed in a membranous web of floating and transparent microbe traceries. This must be where time sifts away from these tunnels into the endless outside.

Grey fibres of mould glowing soft with ‘no-part-of-this’ allure, become the axis of worlds and false memories. Revolving prismatically, they open up in self-dissecting efflorescence. That shivering, glaucous hunger in my flanks. An urge to reach out that is never more than an urge. Twitching, here come the fuzzy vistas of a time before the academy. All the images seem full of dustballs and scratched with turquoise springs. Then all was infant death and nameless. A time of looming portals and tunnels stretching off, vast and unknown. Remember the Atrium of Pendulous Waiting at whose centre was the brittle, zig-zagged fascination of the hybrid glassberry tree? Somewhere, I thought, there must be a world of such trees. Why cultivate such an exoticism here? As if to tantalise and mystify, whatever way the pendulum of decision swung. The oscillating uncertainty, waiting upon the judgement of the many-celled clockwork they called the Examinations, administered by philosophy-suckled masters, themselves bulging with the clockwork of letters, their florid gills and classically-moulded segments like living acid seals, and grasped in their tentacles like fescues, the keys to acid eternity.

As I contemplated her horizontal trance of twisting – slow, pink, glistening, blind – I was aware of two unusual reactions in myself. First was a comparative lack of the usual relief at escaping the vile burden of pregnancy, that consuming catalyst of replication inside. I had known from the start that my opponent would not put up a sufficient fight to inseminate me, so, for all that our copulation had been rich in many unusual elements, it had been lacking in the suspense of competition. Second was a revival of the cold feeling that had flushed through me when I first noticed this creature. I believe there are fixed word compounds to describe this feeling, but I would prefer to describe it afresh with words of my own. It was a kind of reaching out of my emotions, just as my senses reach out. The pathetic state of my victim somehow moved me as if I were viewing myself. And yet the very fact this was another being, infinitely and eternally removed from my understanding, only made this emotion sharper, more exquisite, and harder to endure. Soon as it had come, though, this feeling burst like a bubble. The attainment of purple was yet a long way off. My self-imposed labour had only just begun.

* * * * *

The next stage of my labour consisted of tracking the thing I had made she to her abode. I withdrew from her slug-bloated, vanquished form, which already seemed to teem with the inner-hatching of odious life, like the multiplying bubbles from the mouth of a dying crustacean. Still bedraggled with her acrid discharges, I hid behind some ornamental stalagmites and waited. At length, as if returning from the swampy realms of some I-dissolving, temporary death, a suggestion of focused awareness informed her flops and twitches and she raised herself to an upright position. I say upright, but there was something bowed about her, as if with the weight of her new burden. She swayed a little, seemingly still dazed. With her senses disordered, she did not seem to be aware of my presence. In an attitude of infinite defeat and infinite resignation, she continued on her way, her wriggle full of the same snags that had first caught my attention and which had made her so painfully appealing.

I gave her a considerable head-start. There was no chance of me mistaking her slime-trail. When eventually I did start on that trail, I thought again of the other, metaphysical trail I followed. At some point it had become a little clearer to me, but I still could not trace it to its final destination. That was only as it should be. Perhaps, though, there was no way ahead at all. I was simply taking those turnings which seemed to have about them the deepest glow of purple.

The slime-trail left the old side-burrow and came out on the fringes of a brightly lit commercial district. At first I was disorientated by this sudden shift from soft-hued gloom to dazzling white light. My antennae recoiled and my gills shrivelled. Even when my senses adjusted a little, the activities of the worms to-and-froing in the semi-plaza before me seemed utterly incomprehensible. They descended on the space from long ramps, from bore-holes and wynds, all partaking of the anonymity of elsewhere which was their source. After an interval, rationalisations for their various occupations seeped into my brain; this worm was being re-hydrated, that worm was composing odours at an odour-lamp, this other worm was milking acid glands. Still I reared dumb before this civilised multiplicity, unbounded and undefined by any future as the past is defined by the present. Over all this was impendent a trade and leisure complex of polyhedron cells in three-dimensional tessellation, like a chunk of metal honeycomb that had crashed into the earth. I felt weak and palsied, a mere creature of the caves, suspended amidst nameless things. Does no other feel this way, I wonder, when suddenly confronted with the solid mass of the present?

Taking hold of myself again I remembered my personal mission. I realised that if the she-thing had taken some form of transport from here, particularly if it had been a slime pod, that I might lose the trail. I discovered with some satisfaction, however, that the trail did not even enter the semi-plaza. Instead it smeared off to the left into a ribbed gallery that led eventually to a residential excavation.

The slushy trail was unbroken right to my victim’s apartments. They were of the ambient grotto variety. I reared before an iris-membrane portal in brightly-lit, metal-encased tunnels, surprised that such a malformed creature should inhabit apartments in such a respectable area. Clearly she was a worm of reasonable social status. I could only think that my inference with regard to her exceptional intelligence had been correct. I noted the exact location of these apartments, as well as the date according to sidereal time, and, my business there, for the time being, at an end, I slithered off back to the commercial district I had recently passed.

* * * * *

As I did so I pondered the question of light. When worms are capable of functioning in semi and total darkness, have for the vast bulk of their history, in fact, existed without bright light, what can be the meaning of the modern craze for bathing public spaces in clinical white light? Clearly, any benefits are aesthetic rather than practical. Some worms remind us knowingly that white contains all other colours, implying that it represents the synthesis of all worm thought and experience. I have even heard that some worms have become loath to stray from the light-saturated central areas of Frfrspfshuul. It seems this light gives worms a sense of security, the symbol of our enlightened age. Is this why the memorial of Yqstlss in the Hall of Philosophy is also brightly lit, despite the fact that such lighting would have been unknown to the Grand Philosopharch when shi-he was alive? For myself, I am neither opposed to nor overly fond of the use of white light. I would just like to note that while it makes others feel secure, it makes me feel rootless and alienated.

This feeling bore down on me with some intensity when I arrived back at the semi-plaza and raised my head to take in the great architectural vug of the trade and leisure complex. A rotten hunger had got into me after my exertions. It is at such times of anonymous physicality that I feel most literary. Moments that are lost as soon as they arise. Moments without posterity. Moments of pure waste. Moments such as the allaying of hunger with food, completing a trivial business transaction, feeling the slime of another congeal on one’s skin after sex. I told myself in my weariness that in this sense I was in for a minor literary treat, and reared there proudly for a moment, enjoying the picture of myself in the foreground, the complex the looming background, myself solitary, soiled, with gills dandily plumed and full of the proud swellings of things as yet unwritten.

After slouching faintly up the ramps, automatic and otherwise, that intersected the inside of the complex, I came to a fungus bar that looked suitable. It was an establishment called The Colony. Inside, the general white light of the complex had been dimmed the better to emphasise the polychromatic phosphorescence of the multifarious moulds, fungi and lichens that had been carefully cultivated in the terraced and suspended gardens between the dining areas. The place was seething with customers, more like a newly hatched brood than selected survivors, and their pigmentation squirmed liquidly in social display. The inner walls of this polyhedron were of such blackness that it seemed they were not there at all. Their surfaces were near undetectable, giving only a reflective gleam here and there, and as a result it appeared as if all the gardens and the squillion customers were superimposed garishly upon ultimate nowhere. “Even these nameless squillions are finite,” I thought to myself. An attendant crawled out from the ledger office and approached me. Shi-he was obviously dosed up on the pigmentation inhibitors so common in such service posts, and even wore a dorsal mantle over which played artificial muzak pigmentation. Yet sh-his ventral and anterior colouring, which was still apparent, seemed to me an aggressive mix of red and white.

“I need to check your seals,” shi-he said, extending a braid of slick tentacles.

I retrieved my seal book and my own seal from my pouch and relinquished then to the baffling attendant. Shi-he gave them a cursory inspection, returned sh-his attention to me for a moment of scrutiny whose meaning I could not guess, then crawled back into the ledger office. There, apparently, my seal and book were subjected to closer examination. When the attendant returned I noticed that my seal had not been used. I raised my antennae quizzically.

“No,” said the attendant.

“’No’ is not the answer to my question.”

“No, I cannot permit your partaking of the services and products of this establishment.”

“Is an explanation to be expected?”

I thought I detected a suppressed orange simmering around the attendant’s white mottles.

“There appear to be only two seals in your book.”

“If you inspect it carefully you will be aware that one of those seals belongs to Doctor Jsshloamgs, my mentor.”

“That seal is due to expire.”

“But it has not expired. There is a vital difference there.”

“Your credentials are dubious.”

This remark did not fail to alarm me. I regretted that I too was not under the influence of pigmentation inhibitors. To lose ground in a bluffing match is deadly. I turned away in confusion and let my senses wander flutter-snufflingly over the interior of the bar. They rested finally, flicker-jitteringly, upon a delicate, wispy mould that grew atop a small dais of black crystal. The fibres of the mould were glowing a beautiful moon-dust grey, with the merest suggestion of filmy blue. For a moment this gossamer translucence became a spyglass onto a world of strange longing, where I was lost. Then my senses returned to me. I collected myself.

“One of those seals is fourth and one third level, and judging by the texture of your establishment here, I should not need more. The second seal is from my superior at the seal exchange bureau. I hold a position there. I know something about seals.”

The attendant did not respond. Because of my befuddlement at the exceptional circumstance of being refused service, a suspicion grew on me, turning into fixated conviction, which in retrospect I was to see as a wild misjudgement.

“Do you require money?” I asked.

“Money?” The attendant physically recoiled at this unexpected word.

“There’s no need to be so surprised. It’s common enough to keep some in case of emergencies. If you go to The Crevices they won’t accept anything else. They’re not part of the seal system there.”

It was clear I was only making the situation worse.

“There is no provision made in our accounts for money.”

“Well, then, why not accept my seals? You have no grounds for describing Dr. Jsshloamgs’ seal as ‘dubious’.”

“Business is not as one-dimensional as you think.”

This last insult was delivered in a suppressed hiss. I had been forced into a zone where all dignity was denied me. The vital, naked I flared up from within me, embattled, defending the dignity of its existence beyond dignity.

“Are you questioning my survival skills? You? A purveyor of edible fungi? You who needs pigmentation blockers just to perform your duties? Your type knows nothing of the subtlety of squirming through the sea of bodies that is our race. Uniqueness? Abstraction? It’s quite beyond your sensory range. It would be a satisfactory propriety to take you outside now and inseminate you, but unfortunately I have recently donated. You’d know the tang of my fluids with eggs inside you.”

By this time our altercation had attracted the attention of a number of the guests. I had been unable to keep myself from flashing in a variety of anti-social patterns. I realised it was time for me to cut my losses and leave.

* * * * *

Purple, I say.

The chagrin, the sickness of rearing my conscious head alone. There is a plateau, high and empty. Surrounded only by so far away, so far away, I, uncrowned by the ultimate self that is by right of this existence mine, through tunnels that enclose me in all directions, doppelganger me with strange and isolating limitations, am battered and turned aside. Sashaying, sashaying, squirming, wriggle-looping, blind as the curving tunnels, blind as movement only, sticking with the threads of my skin-slime to the bedrock that remains the same as I forever peel myself away.

Tunnels wander into an abandoned, draughty zone were time is as circuitous as they. Veering up and wide towards the surface to a nowhere hump that I know wordlessly, where the outer light creeps through a crack. Exhausted, I rest. The light that is external to everything I know coats my gills like spittle. I am half absorbed in a membranous web of floating and transparent microbe traceries. This must be where time sifts away from these tunnels into the endless outside.

Grey fibres of mould glowing soft with ‘no-part-of-this’ allure, become the axis of worlds and false memories. Revolving prismatically, they open up in self-dissecting efflorescence. That shivering, glaucous hunger in my flanks. An urge to reach out that is never more than an urge. Twitching, here come the fuzzy vistas of a time before the academy. All the images seem full of dustballs and scratched with turquoise springs. Then all was infant death and nameless. A time of looming portals and tunnels stretching off, vast and unknown. Remember the Atrium of Pendulous Waiting at whose centre was the brittle, zig-zagged fascination of the hybrid glassberry tree? Somewhere, I thought, there must be a world of such trees. Why cultivate such an exoticism here? As if to tantalise and mystify, whatever way the pendulum of decision swung. The oscillating uncertainty, waiting upon the judgement of the many-celled clockwork they called the Examinations, administered by philosophy-suckled masters, themselves bulging with the clockwork of letters, their florid gills and classically-moulded segments like living acid seals, and grasped in their tentacles like fescues, the keys to acid eternity.

Comments:

Post a Comment