Links

- STOP ESSO

- The One and Only Bumbishop

- Hertzan Chimera's Blog

- Strange Attractor

- Wishful Thinking

- The Momus Website

- Horror Quarterly

- Fractal Domains

- .alfie.'s Blog

- Maria's Fractal Gallery

- Roy Orbison in Cling Film

- Iraq Body Count

- Undo Global Warming

- Bettie Page - We're Not Worthy!

- For the Discerning Gentleman

- All You Ever Wanted to Know About Cephalopods

- The Greatest Band that Never Were - The Dead Bell

- The Heart of Things

- Weed, Wine and Caffeine

- Division Day

- Signs of the Times

Archives

- 05/01/2004 - 06/01/2004

- 06/01/2004 - 07/01/2004

- 07/01/2004 - 08/01/2004

- 08/01/2004 - 09/01/2004

- 09/01/2004 - 10/01/2004

- 10/01/2004 - 11/01/2004

- 11/01/2004 - 12/01/2004

- 12/01/2004 - 01/01/2005

- 01/01/2005 - 02/01/2005

- 02/01/2005 - 03/01/2005

- 03/01/2005 - 04/01/2005

- 05/01/2005 - 06/01/2005

- 06/01/2005 - 07/01/2005

- 07/01/2005 - 08/01/2005

- 08/01/2005 - 09/01/2005

- 09/01/2005 - 10/01/2005

- 10/01/2005 - 11/01/2005

- 11/01/2005 - 12/01/2005

- 12/01/2005 - 01/01/2006

- 01/01/2006 - 02/01/2006

- 02/01/2006 - 03/01/2006

- 09/01/2006 - 10/01/2006

- 10/01/2006 - 11/01/2006

- 11/01/2006 - 12/01/2006

- 12/01/2006 - 01/01/2007

- 01/01/2007 - 02/01/2007

- 02/01/2007 - 03/01/2007

- 03/01/2007 - 04/01/2007

- 04/01/2007 - 05/01/2007

- 05/01/2007 - 06/01/2007

- 06/01/2007 - 07/01/2007

- 07/01/2007 - 08/01/2007

- 08/01/2007 - 09/01/2007

- 09/01/2007 - 10/01/2007

- 10/01/2007 - 11/01/2007

- 11/01/2007 - 12/01/2007

- 12/01/2007 - 01/01/2008

- 01/01/2008 - 02/01/2008

- 02/01/2008 - 03/01/2008

- 03/01/2008 - 04/01/2008

- 04/01/2008 - 05/01/2008

- 07/01/2008 - 08/01/2008

Being an Archive of the Obscure Neural Firings Burning Down the Jelly-Pink Cobwebbed Library of Doom that is The Mind of Quentin S. Crisp

Thursday, April 03, 2008

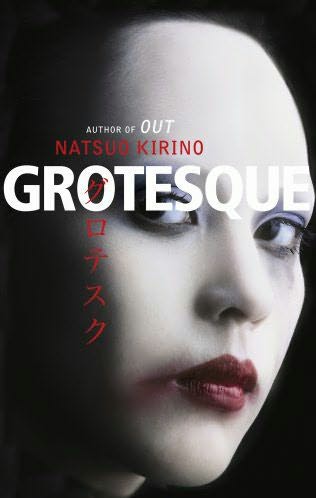

Grotesque

Kirino Natsuo seems to be something of a phenomenon.

She is a Japanese author of, to my knowledge, what might be described as thrillers or crime novels. I know enough to understand that crime is big at the moment. For many horror and supernatural writers, for instance, it's the 'new horror'. I hear murmurings that the crime genre is considered pretty cutting edge right now, and I'm sure there are readers who will corroborate.

Justin Isis turned me onto Kirino Natsuo, describing her as an example of 'obasan rage'. 'Obasan' is Japanese for 'aunt', but is also used to refer generally to middle-aged women.

In London recently, I popped into a bookshop, saw a copy of Grotesque and bought it on impulse. I started reading it that day, and soon found it addictive. Here's what some of the blurbs say:

'Cool, angry and stylish,' The Times.

'Delves so deep beyond its own shock horror premise that much contemporary crime fiction appears cheap and exploitative by comparison...' Metro.

There are more, but I'll leave it at that.

After a couple of days of reading it, I met up with Mr. Wu in London (for those who are new to this blog, Mr. Wu is a pseudonym), and spoke to him about it, even then thinking I'd like to write a review of it.

"It's a Japan I recognise," I said.

"In what way?"

"Well, lots of people made utterly dull and spiteful by conformity."

"Hmmmm. It's funny you should say that. That's exactly, word for word, how I would describe Britain."

(If you're using this blog post for any kind of sociological study, well, I'm afraid that's about as incisive as my social observation is going to get.)

Anyway, the other day I finally finished the book, and now I'd like to write a little about it. I'll try not to give too many spoilers, though I'll have to discuss some aspects of plot. Basically, as explained on the back cover, the story is that of two women educated at the same elite school for girls, who both go on to become prostitutes, and who both are murdered. The story is largely told in the voice of the older sister of one of these women. Ironically, I don't think I can remember the older sister's name now. Damn, that's terrible, and I'll tell you why - because no one really seems to remember her name at all (maybe the author omits it on purpose, but I'm not sure). She lives in the shadow of her younger sister, Yuriko, who is extraordinarily beautiful. People think of her simply as 'Yuriko's (ugly) older sister'. Other parts of the story are told by Yuriko, the second woman, Sato Kazue, and the apparent murderer.

The sister tells us early on that if she had to describe Yuriko in one word, that word would be 'monster'. This seems a startling claim, but she makes good on it as the story unfolds. And the reason her sister is a monster? Not because she was born with an evil soul or any such thing, but merely because of her beauty. Beauty is monstrous because it is the focus of desire, and specifically male desire. This is a book that could be summed up as an unfavourable review of the male sex through the eyes of those most qualified to know them - prostitutes. Kirino Natsuo seems to have arrived on the scene like a brilliant party pooper at an office party, the razor sharp obasan casting a withering eye on the other office girls flattering their bosses and on the bosses simpering in return.

This is a book of unapologetic extremes, successfully pulled off. Just as Yuriko is described straightforwardly as a monster, so society is depicted in more or less absolute terms as a bullying hierarchy, and characters are divided starkly into 'insiders' and 'outsiders', 'sluts' and 'virgins' and so on. Although this could result in a dull simplicity if not skilfully handled, such polarisation is effective here for a number of reasons. The extreme views give a certain incisive power, like the stabs of a sharpened blade. Also, because the story is told from the viewpoints of different characters, and the characters not only reveal different sides of the same events, but different aspects of themselves over time, the narrative blade that Kirino Natsuo uses is not only sharp, but could also be described as double-edged. There's something else, too. Early on in the story, during the section set in the school for girls, where pupils are naturally divided into the 'insiders' who were at the school from the beginning, and the 'outsiders' who enrolled later, there is the following dialogue between the older sister and her best friend:

Best friend: "I didn't think there could ever be such a student here."

Older sister: "Even among the outsiders?"

Best friend: "Outsiders? Damn, you're like an alien, you know. No one laughs at you or tries to bother you. You just go about your business without a care in the world!"

As soon as I read this, and other similar descriptions pertaining to the older sister character, I had a strong feeling that they also applied to Kirino Natsuo as an author. She is 'not even an outsider', and this gives her angle a complexity that belies the seeming simplicity of 'outsider/insider', 'virgin/slut' and so on. It also leads me to imagine the office party that I mentioned earlier as a metaphor for the literary world, full of complacency and mutual back-slapping. I would like to think, and can well imagine, that the presence of Kirino Natsuo makes a lot of the old phoneys in the world of writing and publishing rather nervous. She might just spoil the easy game for everyone, and show up what cheats and slackers they all are.

Although none of the characters in Grotesque are exactly sympathetic, and certainly not admirable, it's definitely men who come off worst:

Being a member of the male sex myself, you might imagine I would find this offensive, but I don't. Not in the least. I'm not sure why that should be except that it simply seems honest to me. It's not some sly political statement, not some part of the power struggle. The main narrator (and perhaps the author) is smart enough to disown any ideology such as feminism. Her hatred is personal, and that's something I can respect completely. In fact, I very much appreciate the opportunity to see the world in such a way, and hope that this is a vista that many men (and women) will find themselves subjected to unwittingly. Even if the picture painted in this book of the male sex is not the 'whole truth', I see no reason to give counter-arguments, which have been given for so long now, anyway, that they resemble excuses. For now, let us bathe in the pure hatred. The hour of obasan rage is upon us!

Yes, indeed, Kirino Natsuo is smart. Her style seems to me like that of someone so sharp she doesn't have to try too hard to prove anything, who can let things drop almost off-handedly here and there. For instance, I love this kind of thing:

What fascinates me is how Kirino Natsuo has taken an angle that is almost the opposite of cool - for instance, the obscure life of the frumpy, middle-aged woman who is the main narrator here - and turned it around to create something that is, to quote The Times once more, "cool, angry and stylish", and how she has done so seemingly without compromise. A work that concentrates solely on hatred, violence and ugliness could be accused of being shallow, and I suppose such a criticism is possible, and yet I feel that there is something in the sharpness and smartness of what Kirino Natsuo has acheived here that is not shallow. Its depth lies in the depth of suffering and the depth of hatred, the care with which the sharp blade of the narrative has been honed, and in all that has been left unsaid.

And, if you want pathos, how about the pathos revealed in small details, such as an aging and 'grotesque' prostitute, of good educational background, putting her finger to her chin as a deliberate expression of little girl cuteness in order to try and win some kind of sympathy from the man who is her oblivious customer?

Not that I would say this is a perfect novel by any means. I did not find, for instance, the narrative voice of the murderer as compelling as that of the older sister. Also, I understand that the author is influenced by Stephen King, and here and there I felt the prose (whether due to poor translation or not, I don't know), lapsed from sharpness into the kind of passable, plodding, action-driven prose characteristic of King. My overall verdict, however, is that I want to read more.

I looked up a little on Kirino Natsuo after I started reading the book. There were two points of interest for me. Perhaps three. I was surprised to find that she is a married mother. I shouldn't have been really. As a writer myself, I know very well that one should not necessarily take fiction at face value or look for a literal correspondence between the work and the author. However, I do admit that I was surprised - but not disappointed. I like the seeming disparity here. I like the fact that she is able so convincingly to project a persona that bears no resemblance to her outward circumstances. Yes, I still believe her work to be honest. Honesty in fiction is something very different to mere autobiography.

Secondly, I noted that although she has written thirteen full-length novels and a number of other books since 1993, only two of her books have been translated into English. This is utterly shameful. I don't know anymore whether to blame the publishers or the reading public for this kind of thing, but it does make me angry nonetheless. The proportion of novels being translated from English to other languages is much greater than the proportion being translated from other languages to English. Why? English literature is so dull and self-satisfied, and so is the English-speaking world. It seems like the only Japanese literature that most people can ever claim to have read (if they can claim any at all) is Murakami Haruki, in whose books, with their offensively coffee-table hip covers, we are currently drowning.

Did I say there was a third thing? Well, just that I looked up some images of Kirino Natsuo, too, and I find she has a rather wonderful face, as you can see above.

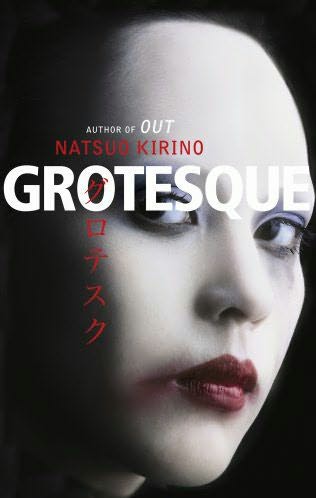

Kirino Natsuo seems to be something of a phenomenon.

She is a Japanese author of, to my knowledge, what might be described as thrillers or crime novels. I know enough to understand that crime is big at the moment. For many horror and supernatural writers, for instance, it's the 'new horror'. I hear murmurings that the crime genre is considered pretty cutting edge right now, and I'm sure there are readers who will corroborate.

Justin Isis turned me onto Kirino Natsuo, describing her as an example of 'obasan rage'. 'Obasan' is Japanese for 'aunt', but is also used to refer generally to middle-aged women.

In London recently, I popped into a bookshop, saw a copy of Grotesque and bought it on impulse. I started reading it that day, and soon found it addictive. Here's what some of the blurbs say:

'Cool, angry and stylish,' The Times.

'Delves so deep beyond its own shock horror premise that much contemporary crime fiction appears cheap and exploitative by comparison...' Metro.

There are more, but I'll leave it at that.

After a couple of days of reading it, I met up with Mr. Wu in London (for those who are new to this blog, Mr. Wu is a pseudonym), and spoke to him about it, even then thinking I'd like to write a review of it.

"It's a Japan I recognise," I said.

"In what way?"

"Well, lots of people made utterly dull and spiteful by conformity."

"Hmmmm. It's funny you should say that. That's exactly, word for word, how I would describe Britain."

(If you're using this blog post for any kind of sociological study, well, I'm afraid that's about as incisive as my social observation is going to get.)

Anyway, the other day I finally finished the book, and now I'd like to write a little about it. I'll try not to give too many spoilers, though I'll have to discuss some aspects of plot. Basically, as explained on the back cover, the story is that of two women educated at the same elite school for girls, who both go on to become prostitutes, and who both are murdered. The story is largely told in the voice of the older sister of one of these women. Ironically, I don't think I can remember the older sister's name now. Damn, that's terrible, and I'll tell you why - because no one really seems to remember her name at all (maybe the author omits it on purpose, but I'm not sure). She lives in the shadow of her younger sister, Yuriko, who is extraordinarily beautiful. People think of her simply as 'Yuriko's (ugly) older sister'. Other parts of the story are told by Yuriko, the second woman, Sato Kazue, and the apparent murderer.

The sister tells us early on that if she had to describe Yuriko in one word, that word would be 'monster'. This seems a startling claim, but she makes good on it as the story unfolds. And the reason her sister is a monster? Not because she was born with an evil soul or any such thing, but merely because of her beauty. Beauty is monstrous because it is the focus of desire, and specifically male desire. This is a book that could be summed up as an unfavourable review of the male sex through the eyes of those most qualified to know them - prostitutes. Kirino Natsuo seems to have arrived on the scene like a brilliant party pooper at an office party, the razor sharp obasan casting a withering eye on the other office girls flattering their bosses and on the bosses simpering in return.

This is a book of unapologetic extremes, successfully pulled off. Just as Yuriko is described straightforwardly as a monster, so society is depicted in more or less absolute terms as a bullying hierarchy, and characters are divided starkly into 'insiders' and 'outsiders', 'sluts' and 'virgins' and so on. Although this could result in a dull simplicity if not skilfully handled, such polarisation is effective here for a number of reasons. The extreme views give a certain incisive power, like the stabs of a sharpened blade. Also, because the story is told from the viewpoints of different characters, and the characters not only reveal different sides of the same events, but different aspects of themselves over time, the narrative blade that Kirino Natsuo uses is not only sharp, but could also be described as double-edged. There's something else, too. Early on in the story, during the section set in the school for girls, where pupils are naturally divided into the 'insiders' who were at the school from the beginning, and the 'outsiders' who enrolled later, there is the following dialogue between the older sister and her best friend:

Best friend: "I didn't think there could ever be such a student here."

Older sister: "Even among the outsiders?"

Best friend: "Outsiders? Damn, you're like an alien, you know. No one laughs at you or tries to bother you. You just go about your business without a care in the world!"

As soon as I read this, and other similar descriptions pertaining to the older sister character, I had a strong feeling that they also applied to Kirino Natsuo as an author. She is 'not even an outsider', and this gives her angle a complexity that belies the seeming simplicity of 'outsider/insider', 'virgin/slut' and so on. It also leads me to imagine the office party that I mentioned earlier as a metaphor for the literary world, full of complacency and mutual back-slapping. I would like to think, and can well imagine, that the presence of Kirino Natsuo makes a lot of the old phoneys in the world of writing and publishing rather nervous. She might just spoil the easy game for everyone, and show up what cheats and slackers they all are.

Although none of the characters in Grotesque are exactly sympathetic, and certainly not admirable, it's definitely men who come off worst:

I can't think of any creature more disgusting than a man, with his hard muscles and bones, his sweaty skin, all that hair on his body, and his knobbly knees. I hate men with deep voices and bodies that smell like animal fat, men who act like bullies and never comb their hair. Oh, yes, there is no end to the nasty things I can say about men. I'm just lucky to have a job at a ward office so I don't have to commute to work every day on the crowded trains. I don't think I could stand riding jammed in a car with a bunch of smelly salary men.

Being a member of the male sex myself, you might imagine I would find this offensive, but I don't. Not in the least. I'm not sure why that should be except that it simply seems honest to me. It's not some sly political statement, not some part of the power struggle. The main narrator (and perhaps the author) is smart enough to disown any ideology such as feminism. Her hatred is personal, and that's something I can respect completely. In fact, I very much appreciate the opportunity to see the world in such a way, and hope that this is a vista that many men (and women) will find themselves subjected to unwittingly. Even if the picture painted in this book of the male sex is not the 'whole truth', I see no reason to give counter-arguments, which have been given for so long now, anyway, that they resemble excuses. For now, let us bathe in the pure hatred. The hour of obasan rage is upon us!

Yes, indeed, Kirino Natsuo is smart. Her style seems to me like that of someone so sharp she doesn't have to try too hard to prove anything, who can let things drop almost off-handedly here and there. For instance, I love this kind of thing:

Yes, I can well believe you don't want to hear any more about my grandfather and Mitsuru's mother and their disgusting love story.

What fascinates me is how Kirino Natsuo has taken an angle that is almost the opposite of cool - for instance, the obscure life of the frumpy, middle-aged woman who is the main narrator here - and turned it around to create something that is, to quote The Times once more, "cool, angry and stylish", and how she has done so seemingly without compromise. A work that concentrates solely on hatred, violence and ugliness could be accused of being shallow, and I suppose such a criticism is possible, and yet I feel that there is something in the sharpness and smartness of what Kirino Natsuo has acheived here that is not shallow. Its depth lies in the depth of suffering and the depth of hatred, the care with which the sharp blade of the narrative has been honed, and in all that has been left unsaid.

And, if you want pathos, how about the pathos revealed in small details, such as an aging and 'grotesque' prostitute, of good educational background, putting her finger to her chin as a deliberate expression of little girl cuteness in order to try and win some kind of sympathy from the man who is her oblivious customer?

Not that I would say this is a perfect novel by any means. I did not find, for instance, the narrative voice of the murderer as compelling as that of the older sister. Also, I understand that the author is influenced by Stephen King, and here and there I felt the prose (whether due to poor translation or not, I don't know), lapsed from sharpness into the kind of passable, plodding, action-driven prose characteristic of King. My overall verdict, however, is that I want to read more.

I looked up a little on Kirino Natsuo after I started reading the book. There were two points of interest for me. Perhaps three. I was surprised to find that she is a married mother. I shouldn't have been really. As a writer myself, I know very well that one should not necessarily take fiction at face value or look for a literal correspondence between the work and the author. However, I do admit that I was surprised - but not disappointed. I like the seeming disparity here. I like the fact that she is able so convincingly to project a persona that bears no resemblance to her outward circumstances. Yes, I still believe her work to be honest. Honesty in fiction is something very different to mere autobiography.

Secondly, I noted that although she has written thirteen full-length novels and a number of other books since 1993, only two of her books have been translated into English. This is utterly shameful. I don't know anymore whether to blame the publishers or the reading public for this kind of thing, but it does make me angry nonetheless. The proportion of novels being translated from English to other languages is much greater than the proportion being translated from other languages to English. Why? English literature is so dull and self-satisfied, and so is the English-speaking world. It seems like the only Japanese literature that most people can ever claim to have read (if they can claim any at all) is Murakami Haruki, in whose books, with their offensively coffee-table hip covers, we are currently drowning.

Did I say there was a third thing? Well, just that I looked up some images of Kirino Natsuo, too, and I find she has a rather wonderful face, as you can see above.

Labels: crime fiction, Grotesque, Kirino Natsuo

Comments:

Post a Comment